About the Helen Clark Foundation

The Helen Clark Foundation is an independent public policy think tank based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, at the Auckland University of Technology. It is funded by members and donations. We advocate for ideas and encourage debate; we do not campaign for political parties or candidates. Launched in March 2019, the Foundation issues research and discussion papers on a broad range of economic, social, and environmental issues.

Our philosophy

New problems confront our society and our environment, both in New Zealand and internationally. Unacceptable levels of inequality persist. Women’s interests remain underrepresented. Through new technology we are more connected than ever, yet loneliness is increasing, and civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite greater awareness. We aim to address these issues in a manner consistent with the values of former New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark, who serves as our patron.

Our purpose

The Foundation publishes research that aims to contribute to a more just, sustainable, and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. We welcome your support: please see our website www.helenclark.foundation for more information about getting involved.

About WSP in New Zealand

As one of the world’s leading professional services firms, WSP provides strategic advisory, planning, design, engineering, and environmental solutions to public and private sector organisations, as well as offering project delivery and strategic advisory services. Our experts in Aotearoa New Zealand include advisory, planning, architecture, design, engineering, scientists, and environmental specialists. Leveraging our Future Ready® planning and design methodology, WSP use an evidence-based approach to helping clients see the future more clearly so we can take meaningful action and design for it today. With 55,000 talented people globally, including over 2,000 in Aotearoa New Zealand located across 40 regional offices, we are uniquely positioned to deliver future ready solutions, wherever our clients need us. See our website at wsp.com/nz.

Whakataukī

He aha te huarahi? I runga i te tika, te pono, me te aroha.

What is the pathway? It is doing what is right, with integrity and compassion.

He mihi: Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following people and organisations who assisted with this work. Ngā mihi nui.

WSP for their ongoing support of the Helen Clark Foundation, and for championing my research for the last two years. This is my final report as WSP Fellow. It has been a pleasure and a fascinating learning curve to work with WSP’s experts on some of the big challenges facing Aotearoa New Zealand. Particular thanks to David Kidd, Bridget McFlinn, and Nic Scrivin for forging such a strong working partnership.

Current and former WSP staff who particularly assisted with this report: Anisha Panchia and the in-house studio team for bringing it to life with stunning design, and Kezia Lloyd, Catherine Hamilton, Michael Campin, Vivienne Ivory, Campbell Gardiner, Graeme Sharman, Louise Baker and Phil Harrison.

Erin Gough for sharing her lived experience in an engaging (and frankly enraging) Q&A on the realities of how the transport system fails disabled people.

Academic experts on the links between transport, equity, climate change, and justice who generously shared their findings and resources and offered valuable insights: Caroline Shaw, Alex Macmillan, Kirsty Wild, and Ed Randal.

The researchers and commissioning agencies behind two reports – Social Impact of Mode Shift (lead author Angela Curl) and Equity in Auckland’s Transport System (lead author Bridget Burdett) – whose findings underpin much of this report.

Independent peer reviewers from the transport and public sectors who offered valuable feedback and strengthened the analysis and recommendations.

The new heads of urban design and transport at Te Awakairangi Hutt City Council, Becky Kiddle and Jon Kingsbury, for a grounding conversation about what an equitable, low-traffic future might look like in my community.

My colleagues at the Helen Clark Foundation for practical, moral, and vital Auckland fact-checking support: Kathy Errington, Matt Shand, Paul Smith, Soraiya Daud, and Andrew Chen.

Glossary of te reo Māori terms1

| Hapū | Kinship group, clan, tribe, subtribe – section of a large kinship group and the primary political unit in traditional Māori society. A number of whānau sharing descent from a common ancestor, usually being named after the ancestor, but sometimes from an important event in the group’s history. |

| Iwi | Extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people – often refers to a large group descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory. |

| Kaitiakitanga | Guardianship, stewardship. |

| Karanga | A ceremonial call of welcome to visitors onto a marae or equivalent venue. |

| Kaumatua | An adult, elder, or elderly person – someone of status within the whānau. |

| Kaupapa Māori | A Māori approach, Māori principles; a philosophical doctrine, incorporating the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values of Māori society. |

| Kōhanga reo | Māori language preschool. |

| Kura | School. |

| Mana whenua | Territorial rights, authority, or jurisdiction over land or territory. Also refers to hapū or iwi with mana whenua, whose history and legends are based in the lands they have occupied over generations. |

| Marae | Open area in front of a meeting house where formal events take place; often used to describe the buildings that make up a place of cultural significance. |

| Papakāinga | Original home, home base, village; in relation to housing, refers to communal housing where whānau who whakapapa to the land can live intergenerationally according to Te Ao Māori. |

| Rohe | Boundary, district, region, territory, area (of land). |

| Takatāpui | A traditional term meaning ‘intimate companion of the same sex,’ more recently reclaimed to embrace all Māori who identify with diverse sexes, genders and sexualities. |

| Te Ao Māori | The Māori world. |

| Te Ara Matatika | The fair path; a path that is right, just, and ethical. |

| Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi (Māori version). |

| Tika | Correct, true, upright, right, just, fair. |

| Whakapapa | Genealogy, genealogical table, lineage, descent. |

| Whānau | Extended family – the primary economic unit of traditional Māori society. |

| Whanaungatanga | Relationship, kinship, family connection; a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides a sense of belonging. |

| Wharekai | Dining hall. |

| Whenua | Land, ground, territory. |

Glossary of specialist terms

| Accessibility | How easy it is for people to participate in society and take up social and economic opportunities, such as work, education and healthcare. Enabling people to access important destinations is sometimes considered the primary purpose of the transport system. |

| Car dependency | When individuals or communities are reliant on cars for mobility. Car-centric urban planning perpetuates car dependency by making it difficult to get around by other modes and prioritising cars in the allocation of street space. |

| Decarbonisation | The reduction of carbon, and the transition to an economic system that specifically reduces and compensates emissions of carbon dioxide. |

| Forced car ownership | When low-income households retain car ownership due to a lack of alternative transport options, even though the associated cost can be a large proportion of the household budget and have negative health and wellbeing consequences. |

| Just transition | Recognises that responding effectively to climate change will involve both opportunities and costs, and that transitioning to a low-emissions economy will only succeed when these costs and opportunities are distributed fairly. |

| Kāinga Ora | Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities. A Crown entity created in 2019 bringing together the former Housing New Zealand, its development subsidiary HLC, and the KiwiBuild Unit. Governed by a statutory board appointed by the Ministers of Housing and Finance. Responsible for delivering the Government’s state housing build programme, upgrading existing housing stock, leading large-scale urban developments including affordable and market housing, and acting as the landlord for social housing tenancies. |

| Mobility justice | An overarching theory that goes beyond distributive approaches to transport to bring into focus unjust power relations and uneven mobility. |

| Net zero emissions | The state at which greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere are balanced by greenhouse gas emissions taken out of the atmosphere. Domestically, it refers to each nation balancing its own emissions with measures to offset them. |

| Te Manatū Waka Ministry of Transport | The Government’s ‘system lead’ on transport, responsible for providing advice on how the transport system needs to change to support the transport needs of New Zealanders and the Government’s signalled priorities. Functions include reviewing legislation and regulation governing the transport system and monitoring and evaluating transport system performance against key indicators. |

| Transport disadvantage | Disadvantage caused by a lack of transport options, for example not owning a car or not living near reliable public transport. |

| Transport equity | When the benefits and costs of transport policies and projects are fairly distributed between different groups. Equitable policies allocate resources according to need rather than treating all groups the same. |

| Transport justice | Benefits and costs of transport policies are fairly distributed, and in addition, decision-making processes are fair, representative, and seek to ensure the transport system meets the basic transport needs of all people. |

| Transport poverty | Poverty induced by people paying more than they can afford for their mobility (for example taking out a high-interest loan to buy a car or spending a high proportion of their income on petrol, bus fares, or other travel costs). |

| Transport-related social disadvantage | Missing out on opportunities (including opportunities for employment and social connection) because of a lack of practical transport choices. |

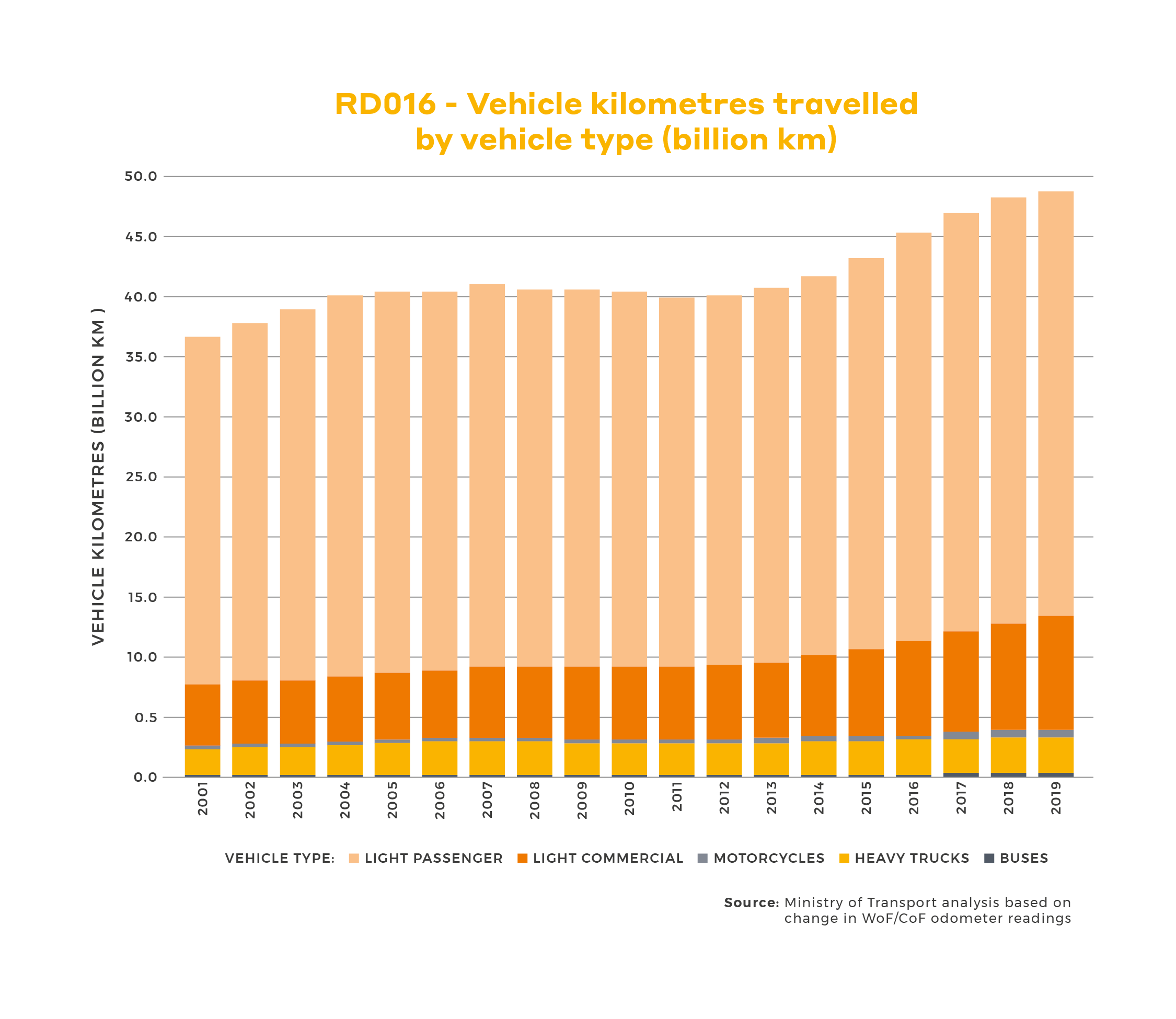

| VKT | Vehicle kilometres travelled – a measure of total kilometres travelled each year by different vehicle types. Can be expressed as a cumulative total (measured in billions of kilometres), or a per capita average. |

| Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency | The New Zealand Transport Agency, a Crown entity governed by a statutory board appointed by the Minister of Transport. Responsible for managing the state highway system, overseeing the planning and delivery of public transport, and managing the funding of the land transport system. Operates at arms’ length from government, but is required to make investments that deliver on the Government’s policy priorities (as signalled in the Government Policy Statement on Land Transport every three years). |

Executive summary

Everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand should be able to get where they need to go affordably, accessibly, and in good time, with a meaningful choice of options that meet their needs, protect the climate, and promote individual and collective wellbeing.

In this report, we make the case that realising this vision (or one like it) should be the primary purpose of the transport system.

At present, our inequitable, car-dominated transport system constrains mobility and limits opportunity for thousands of people and is the second-largest source of domestic carbon emissions. It also kills or injures thousands of people each year, undermines public health, creates harmful air and noise pollution, and is detrimental to our collective mental wellbeing.

To transition to a transport system in which everyone – regardless of income, ethnicity, disability, or gender – can get where they need to go in ways that protect the climate and promote wellbeing, transport policy and investment will need to focus on two things:

- Making the transport system work better for those who are currently disadvantaged; and

- Reducing our collective dependence on cars as our main form of urban transport.

In this report, we set out why transport matters for equity, illustrate why reducing car dependence is the key to decarbonising urban transport, explain the risks of pursuing rapid decarbonisation without adequately considering equity, and lay out a path for how Aotearoa New Zealand can transition to the connected, low-traffic cities we need in the future.

Why focus on cities?

While we acknowledge that there are also significant equity and decarbonisation challenges in rural and provincial transport, in this report we restrict our analysis primarily to urban settings.

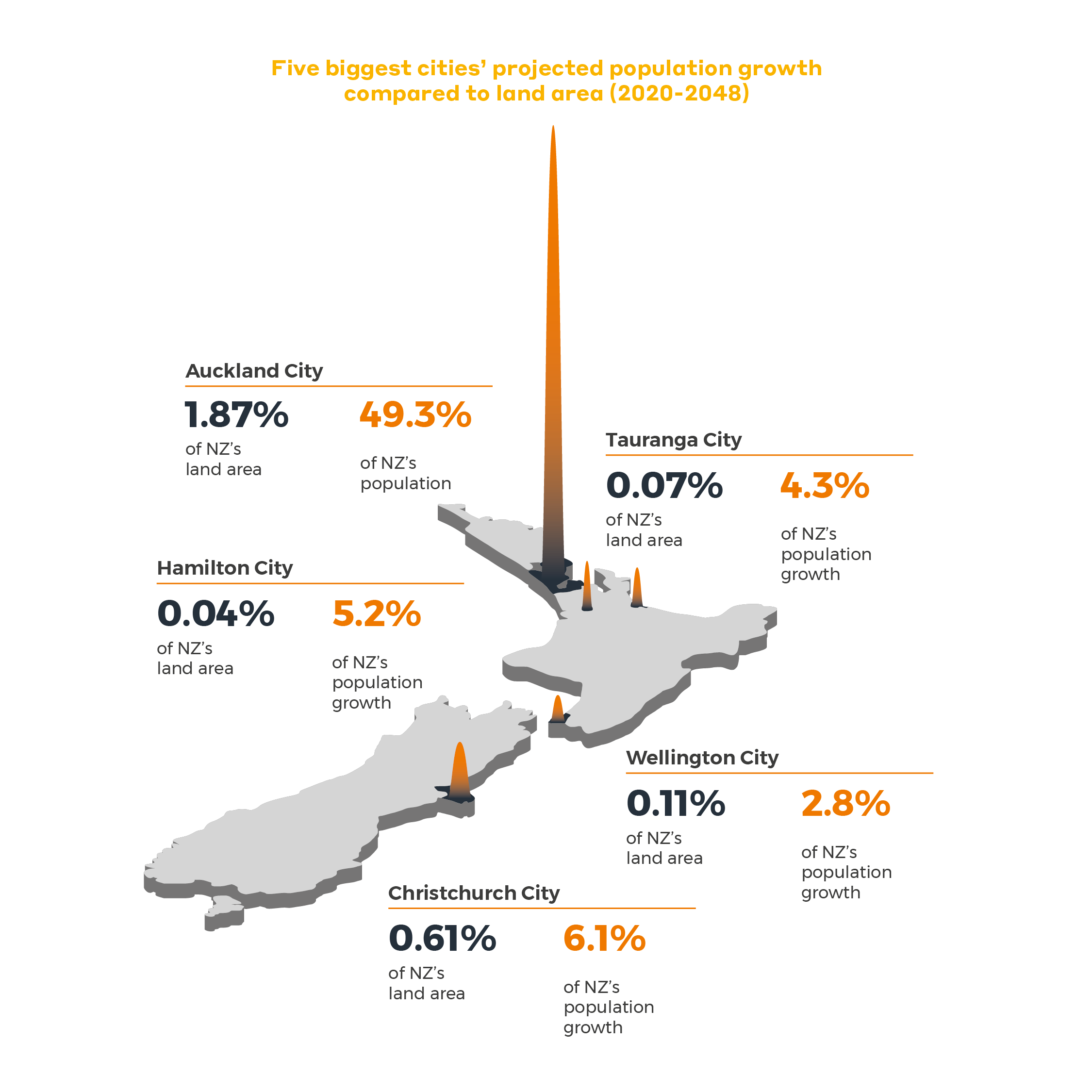

We take this urban focus because nearly three quarters of Aotearoa New Zealand’s population growth in the next 30 years will happen in cities. Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland alone will account for half this growth. By 2048, there will be almost one million more people living in our cities than there were in 2018.

This growth places increasing pressure on our urban infrastructure and creates demand for new and improved transport infrastructure. Te Waihanga, the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, notes that the major challenges facing our cities include:

- High levels of traffic congestion.

- Poor availability of public transport and walking and cycling options.

- Urban design that leads to poor quality-of-life.

These challenges can be addressed by creating connected urban communities that provide greater access to employment, social and recreation opportunities. How the transport system is configured, and what it is programmed to prioritise, will be critical to addressing these challenges.

Why focus on cars?

Aotearoa New Zealand has been committed to the target of net zero emissions by 2050 for several years and entrenched this target in domestic law with the passage of the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019. In late 2021, at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Climate Change Minister James Shaw also committed to reduce New Zealand’s emissions by 50 percent from 2005 levels by 2030.

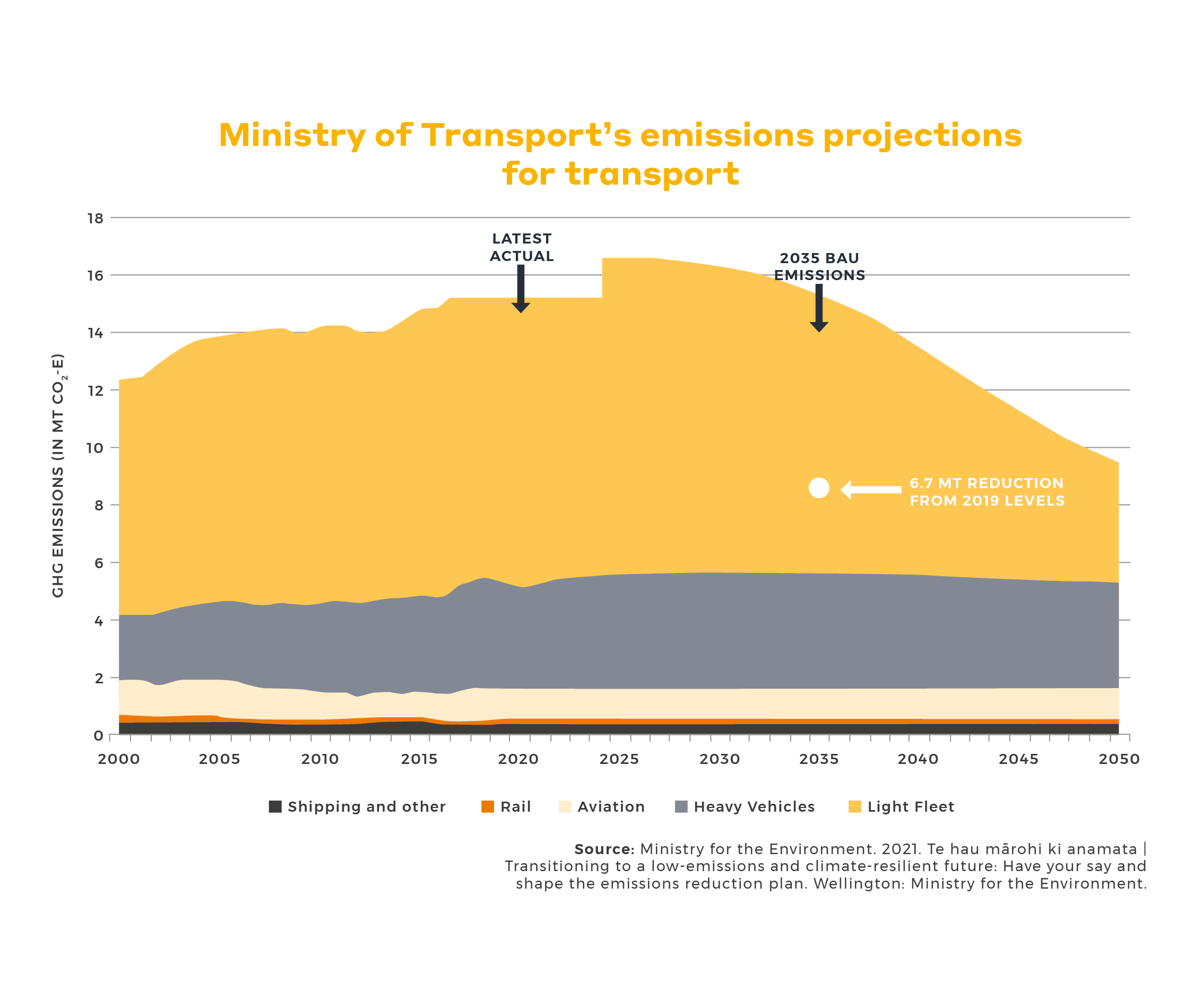

The transport sector is our second-largest source of carbon emissions, and accounts for around 43 percent of domestic CO2 emissions. More than half these emissions come from private vehicles.

Reducing private vehicle use is increasingly seen as a key plank of effective climate change policy. The Government is currently consulting on what to include in its first Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP), and the consultation document identifies “reducing reliance on cars and supporting people to walk, cycle and use public transport” as the first of three target areas for decarbonising transport. It also proposes a specific target to “reduce vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) by cars and light vehicles by 20 percent by 2035 through providing better travel options, particularly in our largest cities.”

It is increasingly accepted by experts and decision-makers that it will not be possible to meet our emissions reduction targets without purposefully reducing widespread car dependence. As the ERP consultation document notes, “the scale of change to achieve these reductions and complete decarbonisation cannot be overstated.”

Why focus on equity?

Our current transport system is not equitable and contributes significantly to wider social and economic disadvantage. Common barriers to mobility in the current transport system include:

- Cost, including the costs of car ownership and maintenance, parking fees and fines, public transport or taxi fares, the initial outlay required to purchase a bike or scooter, or opportunity costs of work forgone due to inadequate transport.

- Accessibility, for example not living close to reliable public transport, not being able to physically board buses and trains, or not being able to drive, walk, or wheel for health or disability reasons.

- Safety, such as the risk of being harassed or assaulted on public transport, not feeling safe to walk or cycle because of traffic, or suffering injury or losing loved ones on the roads.

- Practicality, for example forgoing or delaying a trip because long congestion delays would defeat the purpose, public transport routes or timetables that do not service your destination at the time you need to travel, or having your bike stolen because of a lack of secure storage.

While everyone will experience some constraints to their mobility from time to time, having your mobility consistently constrained creates ongoing disadvantage and poverty.

People experience transport disadvantage when they lack practical transport options, and transport poverty when they are forced to spend an unreasonable proportion of their income on transport. Transport-related social disadvantage is when people miss out on economic and social opportunities because of a lack of transport options.

Those most likely to experience transport-related disadvantage and poverty include Māori, disabled people, people with low incomes, women, takatāpui, queer, and LGBTQI+ people, and members of minority ethnic groups including Pacific people. All these groups experience other forms of systemic disadvantage, and there is considerable overlap between them. The current transport system not only causes inequitable access to mobility but exacerbates wider economic and social inequity.

Achieving transport equity (when the costs and benefits of transport are distributed fairly) and transport justice (when everyone’s mobility needs are met and transport decision-making is fair and representative) will benefit not only those who are currently disadvantaged, but everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Risks of pursuing decarbonisation without adequately considering equity

There are significant risks that decarbonisation in general, and VKT reductions in particular, could be pursued in ways that entrench existing disadvantage. These risks include:

- Costs falling on those already disadvantaged, for example poorly-targeted congestion pricing schemes that restrict the mobility of disadvantaged groups, while having minimal impact on the transport patterns of those with greater resources.

- Benefits accruing to those already advantaged, for example upgrading public transport based on the habits and expectations of advantaged groups or implementing street-level changes that enhance neighbourhood appeal in high-income areas first.

- Unwanted or inappropriate new infrastructure, for example creating new cycle lanes in low-income areas, without first understanding the first-order transport needs of the community or the actual barriers to cycling.

- ‘Baked in’ inaccessibility and unmet need, for example, designing new or improved public transport infrastructure based on current demand, rather than to trying address unmet transport need.

- Gentrification, when street-level changes to increase accessibility and reduce traffic or new public transport connections make previously low-income neighbourhoods more attractive, increase property prices, and displace long-term residents.

These risks – and others associated with an insufficiently equitable climate change response – must be avoided. With Aotearoa New Zealand’s endorsement of the International Just Transition Declaration at COP26, our international commitments now also include a promise to avoid them.

Te Ara Matatika: the fair path

If Aotearoa New Zealand is to honour its commitment to a just transition, achieve transport equity, and meet net zero emissions targets, our cities will need to look very different in future.

Increasingly, international and local evidence suggests the ‘fair path’ leads away from car-dominated cities with a ‘hub and spoke’ model of commuting from outlying suburbs into the CBD, towards connected, localised urban communities in which people can access most of their needs close to home and have ready access to public and active transport options when they need to go further.

Arriving at these equitable, low-traffic cities in the future requires reprogramming the policy settings that govern transport, land use, and urban design now. We need to create urban environments that reduce the overall need to travel, shorten the distances between key destinations, and promote social connection. We also need to overhaul the way we allocate transport investment.

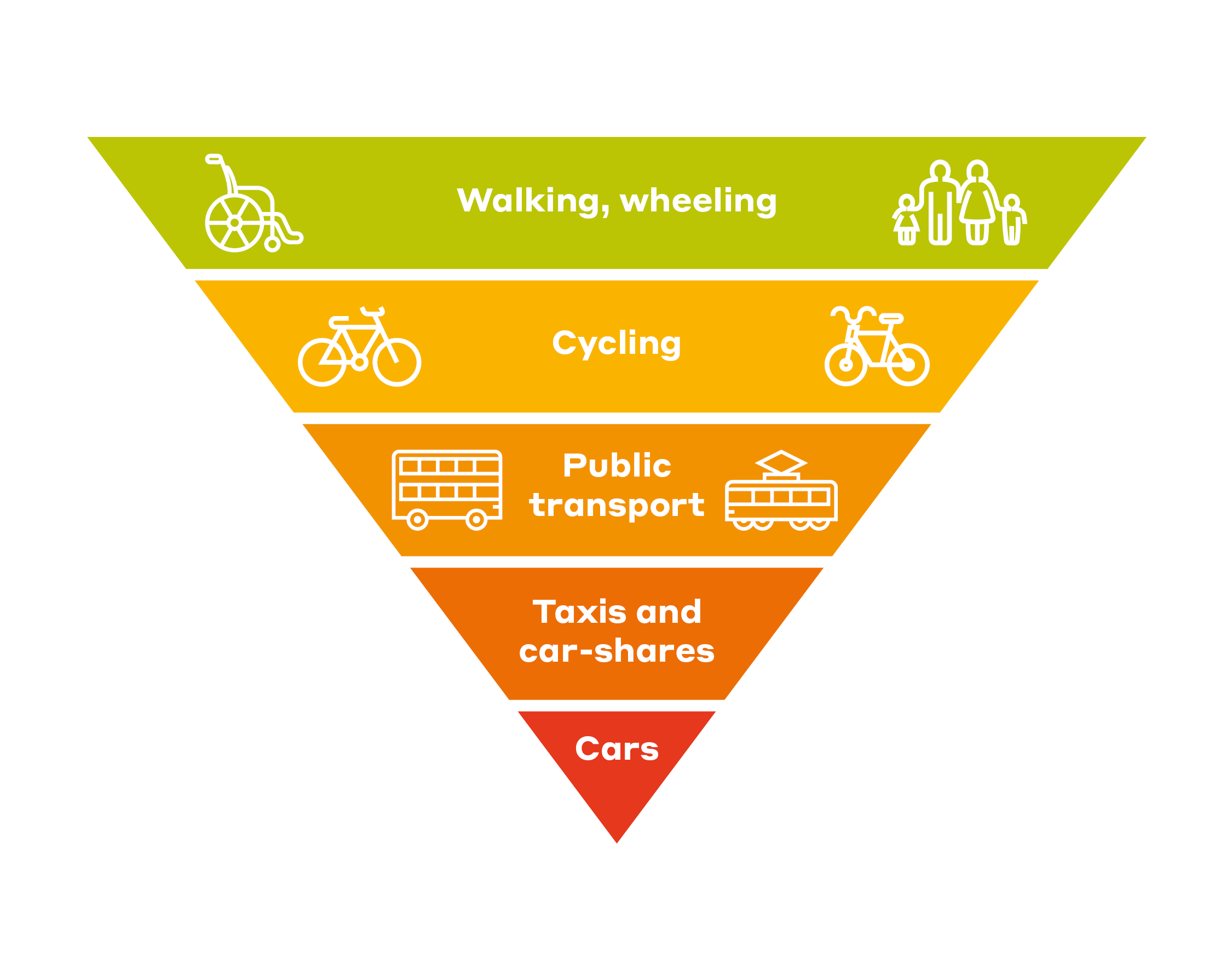

Fair, sustainable transport policy should promote walking, wheeling, public transport, and ride share options above private car use for the movement of people. Transport investment should also be allocated accordingly. Investments that reduce demand for car travel, create active transport infrastructure, improve public transport, and maintain and improve existing roads should take precedence over the creation of new car-dominated transport infrastructure.

Summary of recommendations

We have five overarching recommendations that would help to fairly transition Aotearoa New Zealand’s cities to the connected, low-traffic communities we need for a decarbonised future. Under each, we direct specific recommendations to relevant Ministers and agencies. These recommendations are summarised below, and appear in full at the end of this report.

1. ‘Reprogramme’ the transport system

- Set an ambitious vision for the transport system.

- Make improving equity and reducing car dependence key priorities in support of this vision.

- Integrate this vision and priorities into all relevant transport policies and strategies.

- Introduce legislation to make it easier for councils to make low-traffic interventions at scale.

- Align the road safety strategy with this vision.

- Change how investment is allocated to deliver against these two priorities.

- Require the Ministry of Transport and Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency to use new assessment and decision-making tools that measure equity and VKT impact of transport projects.

- Commission research that fills current knowledge gaps about transport equity.

2. Make sure the transition is tika (right and just)

- Partner with Māori to uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations in the transport system.

- Ensure representation from disadvantaged communities in transport decision-making.

- Apply the principles of a tika transition to all transport and climate change decisions.

- Co-design new urban transport infrastructure with affected communities.

3. Reduce the overall need to travel

- Make reducing VKT an explicit goal of new developments as part of RMA reform.

- Require urban planning that reduces the overall need to travel, shortens distances between key destinations, and promotes social connection.

- Pilot this approach in Kāinga Ora-led developments, using the principles of 20-minute cities.

4. Make sure the costs and benefits fall in the right place

- Ensure future congestion pricing schemes maximise equity.

- Align transport, climate change, housing, land use, taxation, and income policies and coordinate better between government agencies.

- Encourage and fund low-carbon, shared community transport solutions.

- Make sure policies to incentivise mode-shift benefit those who are currently disadvantaged.

- Pilot innovative solutions in a wide range of settings and communities.

- Design transport infrastructure based on unmet need, not current demand.

- Make public transport cheaper and better for low-income communities.

5. Kickstart the transition

- Make a bold intervention to incentivise rapid mode shift, such as making public transport free for a sizeable target group (such as young people under 25 and/or Community Services Card holders).

Two stories to open this report

Hana’s story: 2021

Hana is 21. She lives in Onehunga, in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, with her parents, grandmother, and three younger siblings. Hana is studying full-time to be a social worker at Unitec in Waitākere, which involves face to face classes three days a week, and some distance learning from home.

Hana receives a student allowance of $203.11 a week after tax. She also works ten hours at night, cleaning offices in the CBD. This pays minimum wage and is taxed at the secondary tax rate of 17.5 percent, so Hana gets about $160 a week from this job after tax. She aims to give about $150 a week to her parents to help with rent, food, and power, leaving her with about $210 of disposable income.

Hana commutes to campus three days a week. Driving is much quicker than the two buses it takes to get there by public transport, and at $6-8 a day, student parking is almost as cheap as a return bus fare ($5.50), so Hana decided to buy a car. She had another good reason for this too: her own car offered a safe way to get to and from her late-night cleaning job.

Unfortunately, Hana had a poor credit rating from bad experience with a mobile shopping van a couple of years ago, so her bank wouldn’t lend her $3000 for her 2005 Nissan Teana. Instead, Hana got a loan from a high-interest lender with offices in her neighbourhood. The repayments are $35 a week, and she is paying 20 percent interest. It will take her seven years to pay off the loan, and by then she will have paid a total of $5400. Hana’s petrol costs are about $60 a week.

When Hana bought the car, the registration and WOF were paid in advance. When they expired, Hana paid $30 to renew the registration for three months, but the car failed its warrant because it needed two new tyres. Hana couldn’t afford the $200 right away, so she didn’t buy them.

Hana knew it was a bad idea to drive without a WOF, so she switched to catching the bus to campus. This can be slow in peak hour, especially because she has to change buses on the way, so she leaves home at about 7.20am to get to her first lecture at 9am and is sometimes still a few minutes late.

She tried using public transport to get to her cleaning job too, but the night services are infrequent, and sometimes she waited up to half an hour in the dark. After one nasty experience being followed to the bus stop, she spent $25 on an Uber – losing almost half the earnings from her shift.

Eventually, Hana felt so uncomfortable that she started taking her car to her night job, even though she still hadn’t replaced the tyres. Last week, the inevitable happened: she got a $200 fine for having no warrant, and an additional $150 fine for worn tyres. After her initial despair, Hana negotiated to pay the fines off in instalments – $35 a week over ten weeks.

Now, Hana spends $120 a week on transport-related costs: $50 on bus fares and $70 on repaying the loan and fines for a car she isn’t using. This is about 33 percent of her weekly income. After giving her parents $150 to contribute to the family finances, Hana has $93 left. She spends $10 a week on an endless data plan so she can study online at home (Hana’s family doesn’t have wifi), and tries to put $20 aside for the new tyres, which she’s still hoping to buy.

Hana can’t risk driving again until she has a WOF, so for now she has parked the car on her parents’ lawn. They are not happy about this, and nor is their landlord, but she can’t park it on the street in case she gets another ticket. She is back to catching the train to her cleaning job and feeling unsafe.

Aisha’s story: 2040

Like Hana, Aisha is 21 and lives in a large city with her whānau. They live in a papakāinga community that was built about fifteen years ago as a joint initiative of mana whenua, the council, and Kāinga Ora. Their whare houses Aisha, her mum, and her two siblings, and her grandmother lives nearby in a kaumatua flat that is part of the same development. Aisha’s mum is working towards home ownership, but she will not hold freehold title. If they decide to move in the future, they can cash out the equity they have built up, but not sell on the open market. Other houses and units in the community are social rentals, and most residents whakapapa to mana whenua.

The community produces net zero emissions and there are no cars beyond the perimeter. Aisha’s whānau and their neighbours move between each other’s homes and the communal facilities, which include a wharekai, meeting house, and play area that is visible from all the houses. The wide, covered paths between the buildings allow for walking, slow wheeling (like little kids on bikes and scooters, and non-powered wheelchairs), and faster wheeling (like powered mobility scooters, e-scooters, and bikes).

A few residents have cars, which they park and charge at the perimeter in dedicated spaces (though they pay extra unless they can’t use other transport modes). Most use one of several communal e-vehicles when they need to travel longer distances or transport bulky items. These are also used as community shuttles at nights and weekends, and there is a roster of residents with current drivers’ licenses to do a monthly shift.

There is a bus stop right by the main entrance to the community, and buses come past every 5-10 minutes to service local destinations like schools, the village shopping area, and community facilities. They also connect to the city-wide rail network.

Most days, Aisha takes a bus and a train to get to university where she is studying to be a teacher. The ticketing is integrated. She only waits a couple of minutes to transfer, and as a student, her public transport is free. It takes about 25 minutes.

The suburb is also connected to a wide, separated active travel network. About once a week, Aisha bikes to a park or the beach with her three younger cousins (who also live in the community) to give her Aunty a rest. They can ride two-abreast so they can talk on the way and Aisha can keep an eye on the younger kids.

Aisha receives a student allowance indexed to the living wage that matches the national guaranteed minimum income. She doesn’t need to work on top of this, but chooses to do one shift a week waitressing for a catering company because she is saving for a trip to Rarotonga with her friends to celebrate when they graduate next year. If she finishes work after last bus, or goes out late with friends, she calls the community shuttle and someone picks her up, no questions asked.

Part 1: The Fair Path – why transport matters for equity

Being able to get where you need to go – to get to work or school on time, do your own grocery shopping, go to the doctor when you are sick, or visit your friends and family – is both a basic need, and a human right.2

Everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand should be able to get where they need to go affordably, accessibly, and in good time, every time. Everyone should also have a meaningful choice of options that meet their needs, protect the climate, and promote individual and collective wellbeing.

At the moment, our inequitable, car-dominated transport system constrains mobility and limits opportunity for thousands of people and is the second-largest source of domestic carbon emissions. It also kills or injures thousands of people each year, undermines public health, creates harmful air and noise pollution, and is detrimental to our collective mental wellbeing.

To transition from what we have now to a transport system in which everyone – regardless of income, ethnicity, disability, or gender – can get where they need to go in ways that protect the climate and promote wellbeing, will require future transport policy and decision-making to focus on two things:

- Making the transport system work better for those who are currently disadvantaged; and

- Reducing our collective dependence on cars as our main form of transport.

In Part 1, we address the first of these: a more equitable transport system.

There are thousands of people in Aotearoa New Zealand who live with significant constraints on their mobility. As ‘Hana’s story’ on page 12 illustrates, these barriers can take many forms. Often many are present at once, and they frequently intersect with, and exacerbate, other forms of disadvantage like low-income, inadequate housing, or lack of digital access.

In this Part, we outline some common barriers to mobility in the current transport system, show which groups and individuals are most likely to be affected, and highlight how they contribute to other forms of disadvantage. We make the case that improving equity should be a key objective of transport policy and highlight how everyone stands to benefit from a more equitable transport system. We conclude with the observation that achieving equitable transport outcomes will require changing the inputs used to make transport decisions.

This Part includes a Q&A from Erin Gough, a human rights expert and disability advocate whose experiences highlight how the transport system can restrict disabled people’s mobility and rights.

A note on sources: Under the headings, ‘Common barriers to mobility’, and ‘Whose mobility is constrained’, we draw extensively from two reports summarising available evidence about transport and equity in Aotearoa New Zealand. These are:

- Social impact assessment of mode shift, commissioned by Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency and undertaken by the University of Otago, released September 2020; and

- Equity in Auckland’s Transport System, commissioned by Te Manatū Waka Ministry of Transport and undertaken by MRCagney, released November 2020.

Unless otherwise stated, the information in these sections is sourced from these reports. It would be unwieldy to footnote every instance, but we gratefully acknowledge the authors for gathering this evidence, and the commissioning agencies for making it available. Anyone wanting to learn more about transport and equity in Aotearoa New Zealand should read these reports in full.

Any mistakes in the interpretation of the evidence are ours. Sources other than these are cited fully.

Common barriers to mobility

Cost

Having insufficient income limits many people’s day to day options and activities when they choose not to travel because of the cost. This can be harmful, such as when people forgo essential medical care or keep their children home from school because they don’t have the money to pay for the trip.

But some trips, like commuting to work, can’t be avoided. For this reason, many people end up spending a disproportionately high percentage of their income on the cost of travel, most often by owning a car, even when their budget does not reasonably allow for the costs of petrol, maintenance, registration and WOF updates. This is known as forced car ownership. Very often people will go into debt to purchase a vehicle, so high-interest loan repayments become another inequitable cost of transport.

Other transport-related costs that can be unaffordable for many people include parking fees, fines (especially for lapsed WOF or registration which may not have been paid due to the cost), public transport fares (which cost more for those who can only afford to pay trip by trip than for those who can afford to purchase multi-trip passes), taxi and ride-share fares (which are often not an option for those on low incomes), and the initial outlay and ongoing maintenance costs associated with purchasing an alternative like a bike or scooter.

Accessibility

In a transport context, accessibility refers to the ease with which people can get to the places they need to go to enable them to participate in society, such as workplaces, schools, and healthcare facilities. It refers to all people, although disabled people often experience the most barriers to mobility because of the many ways an ableist society restricts their participation, including in transport.

Many aspects of the transport system can restrict accessibility. For example, someone who lives in an area where there is no public transport within a convenient walking or wheeling distance is experiencing an accessibility barrier. Likewise, someone might live within a reasonable distance of a public transport service, but not be able to use it because of physical accessibility issues, like steps up to train or bus stops for wheelchairs or buggies, or insufficient seating on buses or trains for pregnant people, older people, and those with chronic health conditions. Some public transport options are only accessible to a limited number of travellers, like buses with only one or two spaces for wheelchair users, or seats that are not wide enough for large-bodied people. See the Q&A with wheelchair user and human rights expert Erin Gough on page 18 for an illustration of some of these accessibility barriers in the public transport system.

Non-physical accessibility barriers include complex or confusing timetable, fare, or ticketing information (known as ‘wayfinding’ information). This can be challenging for both children and older people, people with low vision or hearing impairments, speakers of English as a second language, or people with intellectual impairments. Likewise, noisy, crowded, or overwhelming street or public transport environments can also be triggering or dangerous for very young or older people, people with neurodiverse conditions like autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), or sensory processing disorders, and people with some mental health conditions (like anxiety or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)).

Even driving can be inaccessible – some people have health conditions or impairments that make operating a standard car difficult or impossible, older people may lose their drivers’ licence, or extreme congestion or busy traffic conditions may make driving impractical or unsafe for some.

Safety

Road traffic kills and injures thousands of people in Aotearoa New Zealand every year. On average, one person is killed on our roads every day, and another is injured every hour, an unacceptable situation that creates huge health, social, and economic costs for society, as well as causing untold grief and stress for thousands of families.

Fears about road safety constrain some people’s independence by discouraging them from driving on particular roads or in particular conditions, but more than that, safety concerns also govern many people’s decisions about transport mode, discouraging them from walking and wheeling or allowing children to use these modes. This can create an unfortunate vicious cycle where some people avoid active modes because high traffic volumes make these modes unsafe, in favour of driving, which of course contributes to the perceived safety problem.

Even on footpaths, non-car hazards can discourage people from walking regularly. Many urban areas are not well-equipped for pedestrians, either with no footpaths (as in some light industrial areas), or footpaths that are poorly-lit, not wide enough, or cluttered with obstacles like parked cars, business signs, and poorly-positioned trees or plants. Furthermore, cars are prioritised on most roads, and genuinely safe, separated cycle lanes are rare. This means footpaths are often used by other ‘wheelers’ – skateboards, scooters and e-scooters, children on bikes, wheelchairs, and mobility scooters. These are important active modes that should be encouraged, but when crowded onto footpaths with pedestrians, they can create additional hazards that make walking dangerous or intimidating, especially for young children, older people, or those with underlying health conditions.

Hazards from accidental collisions are not the only safety barrier that can constrain people’s mobility. Bullying, harassment, and violence in public spaces are real risks for some people and can constrain their transport choices. For example, having to wait for a long time for a bus or train at night can put women, LGBTQI+ people, and some ethnic minorities at increased risk of targeted violence, including sexual violence, and even when on board a service, harassment and threatening behaviour can occur.

Practicality

Similar to accessibility barriers, there are some features of our current car-dominated transport system that work to constrain the mobility and limit the transport options of many people. While driving or taking an alternative mode of transport might technically be possible for people in these situations, the actual lived experience of doing so may be so inconvenient, slow, or stressful that in practice, these situations are acting as barriers that constrain people’s mobility. As with all the barriers outlined in the previous sections, these factors tend to apply disproportionately to groups or individuals who may already be experiencing multiple forms of disadvantage.

For example, current public transport routes and services have generally been designed to service a particular type of traveller: weekday commuters travelling from outer suburbs into urban centres during morning and evening ‘peak’ times. People who work part-time and want to commute by public transport can find themselves faced with long waits for infrequent services outside of peak hours and opt for the immediate convenience of driving instead. Similarly, those who work in multiple locations, such as home carers, resource teachers, or tradespeople are unlikely to be able to access frequent public transport services that can connect them from one work location to the next without causing unreasonable delays and disruptions to their work hours.

People outside the paid workforce also have transport needs that are not well supported by current public or active transport infrastructure. This group includes at-home parents who may need to travel with one or more children, make multiple stops to do drop-offs and pick-ups, and bring bulky items like pushchairs and nappy bags, making public transport a logistical headache. Even the brave parent who is confident cycling with children may find that existing cycle lanes and shared paths are impractical, not being wide enough to accommodate a trailer or older child riding alongside, or with gates or barriers designed to keep motorised vehicles off shared walking and cycle paths actually preventing larger cargo and passenger bikes from using these facilities.

One practicality barrier that impacts almost every type of traveller is the excessive delays and long journey times created by high traffic volumes. Most city-dwellers, especially those in Tāmaki-Makaurau Auckland, will have stories of long car or bus trips spent stuck in traffic, being made late for work or school or missing important appointments, and arriving at their destination stressed and anxious. Many will also describe actively choosing not to travel at certain times of day, or forgoing work opportunities or social events because they determined that the inconvenience and stress of navigating highly congested roads to get there was not worth the benefit.

“I can never just expect to be able to get where I need to go”: Q&A with Erin Gough

Erin Gough is a senior advisor and child rights lead at the Office of the Children’s Commissioner. Born in South Africa, Erin spent her high school and university years in Ōtautahi Christchurch before moving to Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington in 2015. Erin has worked in legal, advocacy, and policy roles in the community and public sectors. Disabled since birth, Erin is a strong advocate for the rights of disabled people.

Erin, you’re a wheelchair user who commutes daily into the CBD. Can you talk us through a typical day from a transport perspective? How accessible is your commute?

When everything goes to plan, it’s fairly accessible! But this relies on several factors, like:

The local mechanic not having cars they’re working on parked over the footpath. If this happens, I have to yell out for them to move the cars and by the time I’ve done that, I’ve often missed my bus.

There being no prams or wheelchair users on the bus already. Even though there are theoretically two spaces, there is usually not enough room for me to get past into the other one, because I have a bulky power chair. One of my flatmates also uses a power chair, which means we usually take separate buses if we go out together (yes really). On older buses, I sometimes have to reverse down the aisle and off the ramp because there is no turning space. This feels stressful and unsafe!

An accessible bus stop. Due to Wellington’s geography, there are quite a few stops that I can’t get to – up or down steps, on steep hills, and so on – so I sometimes use the stop before or after the one I actually need and take a longer route.

The bus actually stopping. This hasn’t been a problem in the last few years, but I have had awful experiences in the past when drivers would pretend not to see me and leave me waiting because they didn’t want to stop and put out the ramp.

What about outside of your commute – how easy is it for you to access transport for activities in your down time?

Fairly difficult! Especially if I want to go somewhere that doesn’t have a direct bus route, or go with my wheelchair-using flatmate. There is a huge shortage of accessible taxis, especially in Wellington. None tend to operate past about 6pm unless I book days in advance, and even then, there’s no guarantee. This is hugely limiting and has been the cause of many missed events when figuring out the logistics was just too stressful. As you can imagine, it is not conducive to down time at all.

A few years ago, a flight I was on was so delayed that by the time it landed in Wellington, the airport bus had finished for the night. I phoned everywhere trying to find an accessible taxi, and in desperation, ended up paying $200 for a driver from the Kāpiti Coast. There was a media story about it later and some people commented that I should have planned more carefully! I still get angry thinking about it.

Based on your observations, roughly how much time and mental load do you spend planning your mobility compared to what a non-disabled person might?

As you can see from my responses, I can never just expect to be able to get where I need to go, like non-disabled people can. I spend at least some time planning every trip. If it’s just my regular commute, I will build in time in case any of the things I listed in the first question happen, but it is generally quite automatic.

If I’m going somewhere less familiar though, I spend significant time researching the route, the topography, the types of buses, and how often they come. Going out as a flat requires even more planning, since we usually need to take separate buses. If we’re lucky, one of us will only be left waiting for the others for a few minutes; if not, it could be fifteen or twenty.

There’s no longer a direct bus to the airport, so if I’m flying, I plan weeks in advance, usually choosing my flights based on when I’m most likely to get a taxi. In April, I went to Queenstown with two friends, one of whom also uses a wheelchair. I contacted a local company and was told there was only one accessible taxi and it could only take one wheelchair. In the end, we hired an accessible taxi from Christchurch. We paid for someone to drive it to Queenstown, and then my friend drove it for the week. It was pricey, but worth it for the freedom. This is a classic example of a crip tax.3

You’re also a human rights expert – how well do you think Aotearoa New Zealand’s transport system upholds the rights of disabled people to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life?

Not well. Not having accessible transport has huge impacts on where people can live and what kind of life they can lead. These issues are exacerbated in rural areas and small towns, where many people have no accessible public transport options at all. There is also a complete lack of accessible transport options between cities and towns; none of the InterCity buses are wheelchair accessible. And of course, accessibility is not only about wheelchair access, but also things like visual and audio announcements and timetable information in accessible formats like Easy Read.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities says States should ensure disabled people have equal access to transportation. New Zealand is clearly falling well short of this obligation, despite ratifying the Convention in 2008.

The Human Rights Commission held an inquiry into accessible transport in 2005 which found disabled people faced acute, ongoing difficulties. While there have been small improvements, most of the recommendations from its report still apply sixteen years on, which is depressing.4

In this report we advocate for policies to reduce New Zealanders’ collective dependence on cars. Can you see any potential fishhooks for disabled people in these kinds of policies?

Yes. While these sorts of policies are clearly important, often they forget to take disabled people into account and end up further isolating an already marginalised group.

For some disabled people, a car is very much a mobility aid, and should be treated as such. I think the solution is to encourage non-disabled people for whom cars are a ‘nice-to-have’ to use them less by providing solid public and active transport infrastructure, rather than making disabled people ‘prove’ they need a car. I’d like to see lots of practical, accessible alternatives to driving, so that we can assume without judgement that anyone using a car has a good reason.

For more from Erin, follow her on Twitter or read her personal essay “Repairing ‘an invisible coat of shame’” on the RNZ website.

Whose mobility is constrained?

Everyone will experience some barriers to mobility at different times and may decide to temporarily vary or alter their travel decisions accordingly. In 2019, 10 percent of adults reported being unable to make a beneficial transport journey in the past week, due to cost, time, lack of transport and/or too much traffic. This gives an indicative snapshot of how people’s mobility is constrained at any given time.

The odd deferred journey due to temporary, external conditions is no big deal, but some people and groups are much more likely to experience multiple, ongoing, and compounding mobility barriers that restrict their mobility in a more permanent way. The result is an inequitable transport system that disproportionately restricts the mobility (and thus reduces the employment, education, social, and cultural opportunities) of already disadvantaged people.

Those most likely to experience ongoing transport disadvantage and poverty include: Māori; disabled people; people on low incomes or who live in low-income areas; women; takatāpui, queer and LGBTQI+ people; new migrants and ethnic minorities; and Pacific people. Often people will belong to more than one of these groups and may experience overlapping and compounding transport inequity as a result.

Māori

Globally, indigenous populations contribute little to carbon emissions, and tend not to have benefited equitably from the mobility that has caused these emissions. Despite this, they are often most likely to experience transport-related disadvantage and poverty, and may be especially vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change. This arises from a combination of the inter-generational impacts of colonisation, and contemporary policies and practices that fail to adequately consider, uphold, or address the needs of indigenous people.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Te Tiriti o Waitangi creates obligations on the Crown to recognise and uphold the rights of Māori as tangata whenua and ensure that public policy and services (including the transport system) deliver equity for Māori. This is not being achieved at present. While there are gaps in data and research specifically about Māori and transport, the available evidence points to a situation in which Māori experience disproportionate disadvantage and harm in the transport system compared to non-Māori.

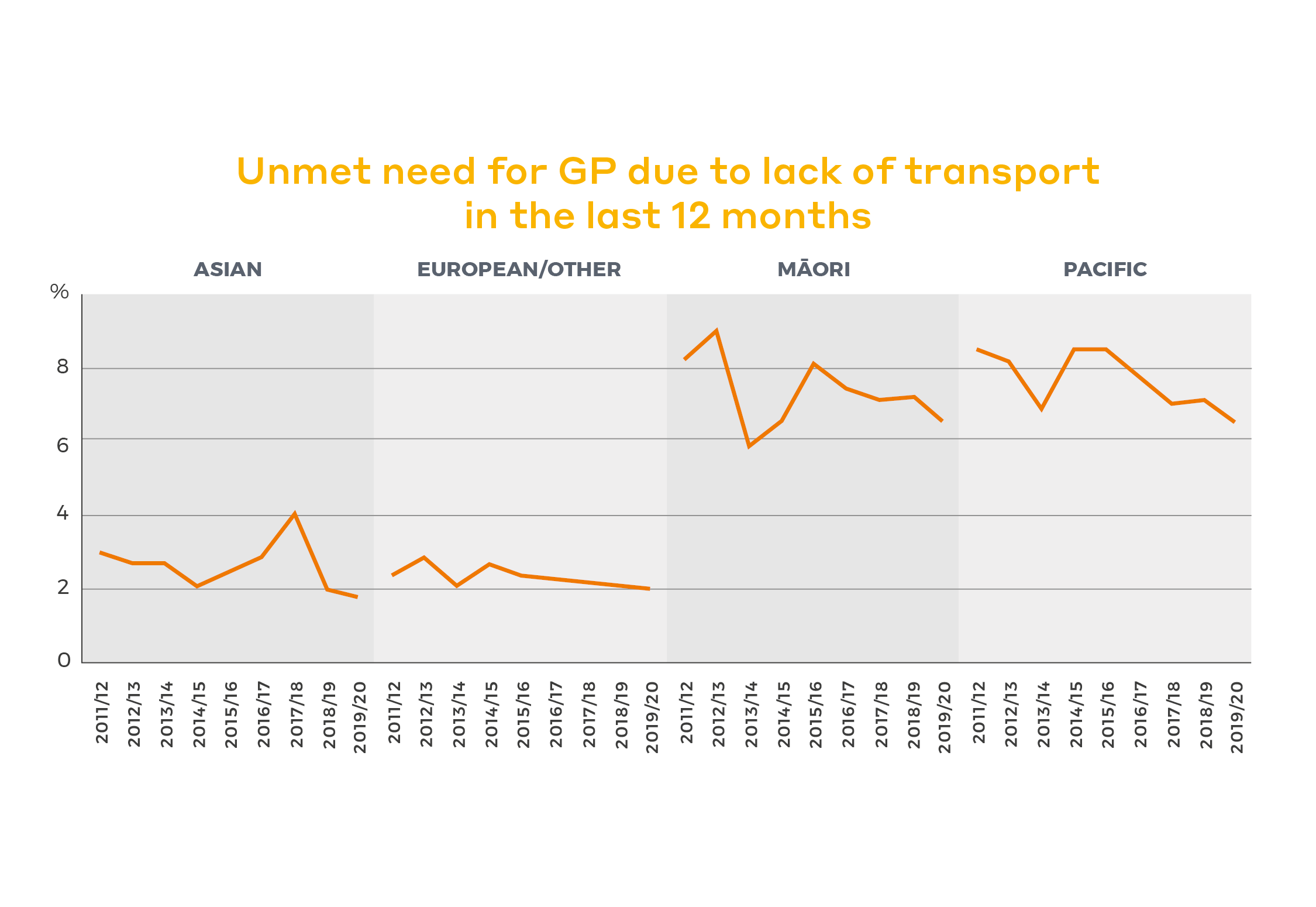

Māori are much more likely than non-Māori to live in low-income households, meaning they are more likely to experience transport poverty and cost-related barriers to mobility. Māori are more likely than non-Māori to go without seeing a doctor due to a lack of transport. This not only creates a transport disparity but contributes to the well-documented health disparities and lower life expectancy that Māori also experience on average.

There are also pathways from transport disadvantage to the criminal justice system that disproportionately affect Māori. Research suggests that, due to cost, Māori (particularly Māori men) may be more likely than non-Māori to drive without a licence or drive unregistered or unwarranted vehicles. Sometimes this is done to meet their own urgent transport needs, and often to support the needs of whānau.5 Unfortunately, Māori are also more likely to be stopped by Police than non-Māori and thus more likely to be issued with fines for relatively minor traffic infringements which, if they go unpaid, can eventually result in imprisonment. According to the Howard League for Prison Reform, 65 percent of Māori offenders have a driving offence as part of their initial prison sentence, and about 5 percent of all sentences are just for driving without a licence.6 On top of that, around 80 percent of employers require a current drivers’ licence as a condition of employment, so Māori finishing prison sentences or who have lost their licence as the result of a driving offence can face an additional barrier to reintegration.

Māori also experience major inequity in road safety outcomes. Because they are more likely to experience low income, Māori are less likely than non-Māori to own a vehicle, and the vehicles they do own are more likely to be old and unsafe compared to more modern vehicles. Māori of all ages face higher risk of road trauma than all other ethnicities, likely due to a combination of higher rates of travel in less safe vehicles, lower levels of driver education, and higher exposure as a pedestrian because of lack of access to cars.

Finally, Māori have higher rates of disability than any other ethnic group, which as we will see in the next section also disproportionately predisposes them to transport poverty and transport-related social disadvantage. The net effect is that many Māori experience multiple, intersecting risk factors that restrict their mobility and contribute to other forms of disadvantage.

Disabled people

In her contribution to our April 2021 report about pandemic loneliness Still Alone Together, Disabled Persons’ Assembly NZ Chief Executive Prudence Walker explained the ‘social model’ of disability:

“As disabled people, we are not disabled by our bodies but by society and the constructs (physical, social, attitudinal, informational) within it. [The social model of disability] places the responsibility on society to create a non-disabling world and not [on] individuals who live with impairments.”7

The transport system is unfortunately a major source of exclusion for disabled people, and this can take many forms. Some disabled people have impairments that mean driving is their only transport option. Because disabled people are much more likely than non-disabled people to live on low incomes, this places many in a situation of forced car ownership and transport poverty. For others, their only option may be to be driven by others. While subsidies are available through the Total Mobility scheme to reduce the cost of taxis and public transport for people in this situation, even a half-price taxi can be out of reach for someone on a very low income, and many people report availability issues when trying to book a taxi through this scheme.

Another group of disabled people are those who do not drive, either because their impairments prevent it, or because the costs of car ownership are too high. These people are heavily reliant on public transport. Yet as illustrated by Erin Gough on page 18 public transport is often inaccessible to disabled people, including: physically inaccessible bus stops or train stations; public transport vehicles with limited seating for wheelchair users or inadequate seating for those with invisible, chronic, or underlying impairments; timetable, fare, and ticketing information and systems that are hard to read or overly complicated for those with hearing impairments, low vision, or intellectual impairments; and crowded, noisy, or overwhelming transport environments that are triggering or overstimulating for those with neurodiverse conditions. These factors likely prevent many disabled people from travelling as often as they would like to, and contribute to the compounding systemic barriers that keep many disabled people underemployed, socially isolated, and excluded them from society. This is known as transport-related social disadvantage.

Active transport is another area in which many disabled people are effectively excluded. Some disabled people can use the limited active transport infrastructure we currently have, but others could make greater use of active transport modes if footpaths, cycle lanes, and shared paths were designed with disabled people in mind. This could include wider cycle lanes for those with modified bikes, less cluttered footpaths with fewer hazards for those with low vision, safe spaces for wheelchairs or mobility scooters (either wider footpaths or genuinely shared lanes that make adequate provision for mobility aids as well as bikes), and better aural cues and soundscaping to help people with hearing impairments to navigate urban spaces.

One major gap in our knowledge about disabled people’s transport needs (and other forms of transport inequity) is that we do not collect good data about the trips that people forgo because of a lack of transport options. While we know from qualitative studies and statistics about disabled people’s general wellbeing that this is an important issue, there is not enough sound data about unmet transport need to enable transport planners to model the likely effects of a more accessible public transport system on disabled people’s mobility or increased total patronage.

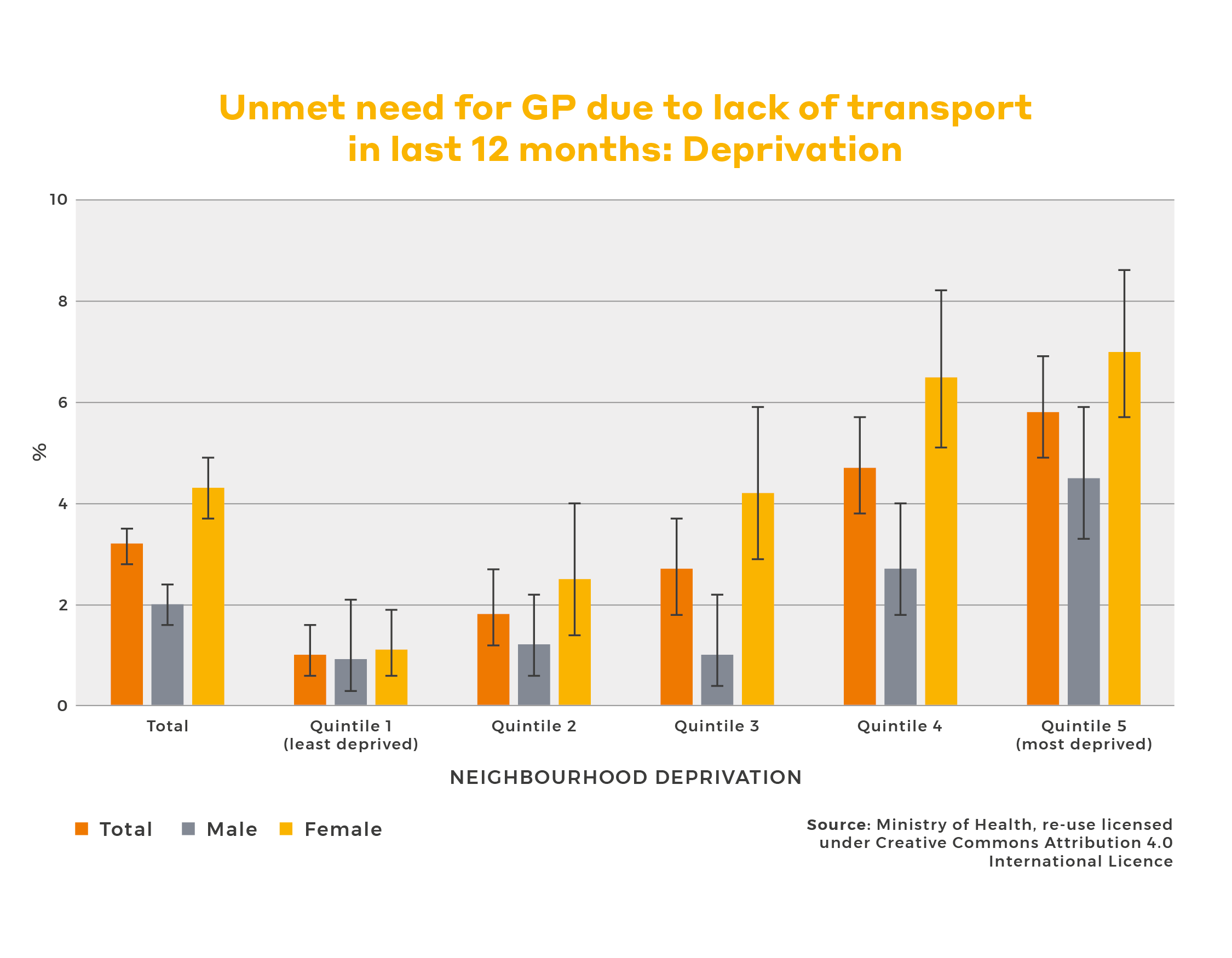

People on low incomes (or who live in low-income areas)

Low income is a leading cause of transport inequity, disadvantage, and poverty. People living on very low incomes are more likely than others to forgo necessary trips because of cost, whether this is the cost of fuel or public transport. They are less likely to have access to a vehicle, and (on the flipside of the same coin) are also more likely to experience forced car ownership because of a lack of realistic alternatives.

As an example, on any given day, driving may be the only available option for someone on a very low income, because it does not incur immediate cost. While the actual cumulative costs of fuel and car maintenance may make driving more expensive on a per-trip basis than a bus or train ride to the same destination, those costs are hidden and deferred. Public transport requires on the spot payment (whether in cash or with a topped-up card), and for many people on low incomes, this is a challenge. In fact, people on low incomes often pay more than people with higher incomes to use public transport, because they are more likely to purchase single fares than buy discounted multi-trip tickets, monthly passes, or make large top-ups on an electronic ticketing card. In this way, multi-trip fare subsidies can make it harder for people with low income to get around, require them to spend more on travel than others (in both real and proportional terms) and, perversely, reward those who can reasonably afford to pay more upfront with the cheapest travel.

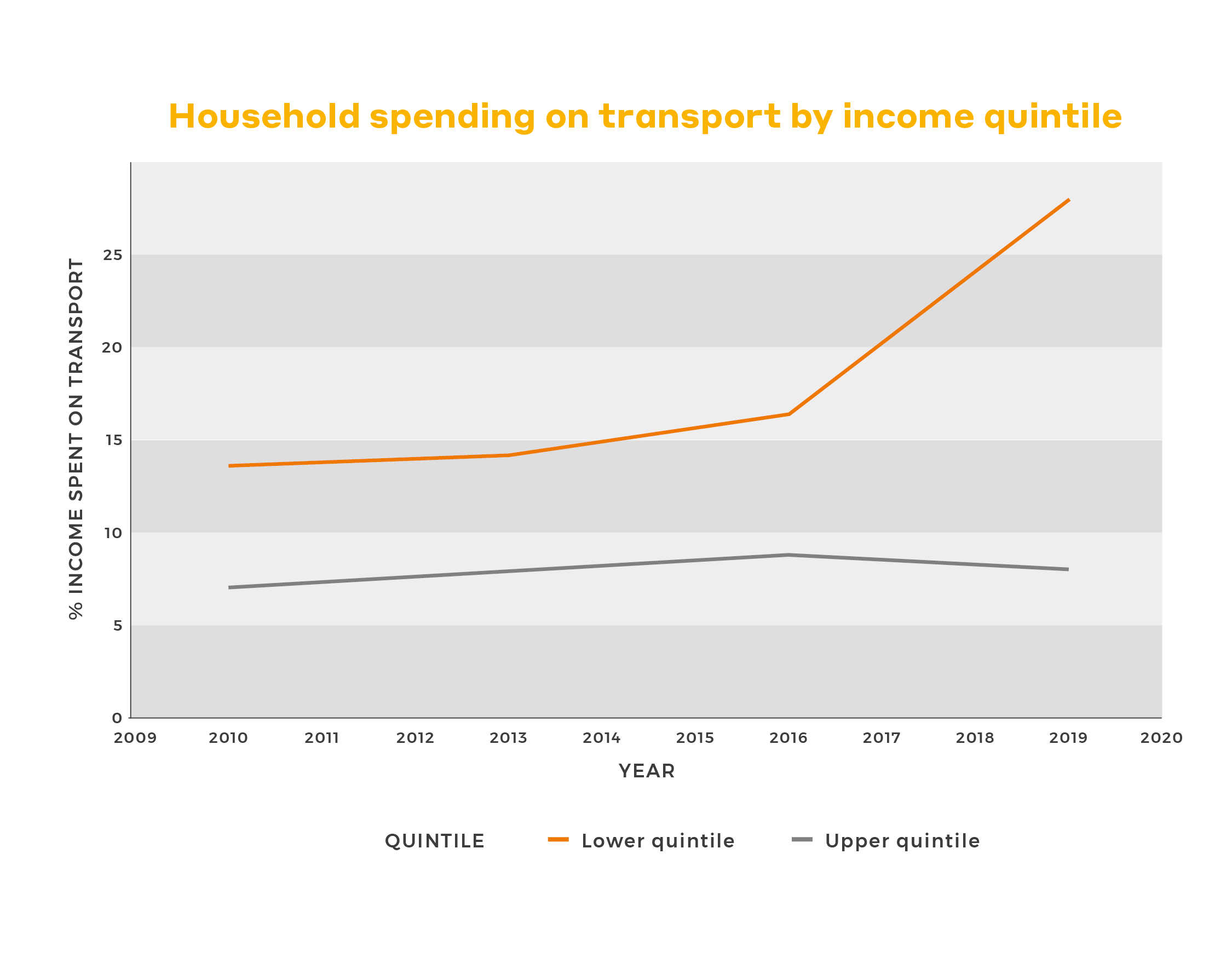

There is significant disparity in the proportion of income that low-income households spend on transport compared to high income households. In 2019, households in the lowest income quintile spent 28 percent of their household budget on transport, while those in the highest quintile spent just 8 percent.8

While it had been the case since at least 2010 that low-income households spent a greater proportion of their income on transport than high-income households (by a margin of roughly 6 percent), the gap has widened rapidly since 2016, with the transport spend of high-income households falling slightly, while that of low-income households steeply increased. It is not clear exactly what precipitated this dramatic change in 2016. Petrol prices experienced a reasonably sharp rise around that time, as did housing unaffordability. More low-income households may have moved out of urban centres in search of affordable housing, creating longer travel distances. More research is needed to understand exactly what caused and continues to drive this widening inequity in transport spending.

While it had been the case since at least 2010 that low-income households spent a greater proportion of their income on transport than high-income households (by a margin of roughly 6 percent), the gap has widened rapidly since 2016, with the transport spend of high-income households falling slightly, while that of low-income households steeply increased. It is not clear exactly what precipitated this dramatic change in 2016. Petrol prices experienced a reasonably sharp rise around that time, as did housing unaffordability. More low-income households may have moved out of urban centres in search of affordable housing, creating longer travel distances. More research is needed to understand exactly what caused and continues to drive this widening inequity in transport spending.

As well as spending a greater percentage of their income on transport and sometimes paying more per trip than those with greater financial resources, people whose mobility is constrained by cost are also likely to pay more for basic consumer items. They are more likely to purchase food and groceries from local dairies and convenience stores that charge high mark-ups, and may also purchase household items like clothes, small appliances, and gifts from mobile shopping vans offer low or no-deposit upfront but charge extremely high compound interest. Such purchases can fuel a further cycle of financial stress for many families.

There are also disadvantages to living in a low-income area (which is mostly, but not entirely correlated with having a low income). Across Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, only a little over 40 percent of people live within walking distance of public transport; this tends to be worse for people in low-income areas. A 2019 study measured public transport connectivity in Auckland based on the extent of train and bus services, stops, and stations, and concluded that, on average, people in low-income areas had poorer connectivity and were more likely to live further from their destinations, face longer journey times, and need to transfer between services to reach their destinations.9 Current farebox recovery requirements incentivise public transport operators to focus on profitable high-patronage routes over meeting the unmet transport needs of disadvantaged communities.

By contrast, people with high incomes are more likely to benefit from public transport, because they are more likely to live within walking distance of a stop, be able to reach their destination with a single trip, and be served by more frequent and reliable services. They also tend to be more vocal in requests for improvements, more likely to participate in consultation, and more likely to vote in local and national elections. As a result, they may be the first to benefit from network improvements or new services, even if the unmet need is higher in low-income areas.

Low-carbon, shared community transport solutions

‘Community transport’ refers to volunteer-based transport services that are specifically designed to meet the needs of a particular group. There are a huge range of activities captured under the umbrella of community transport. Examples include:

- Schools with teen parent units that provide a shuttle service to bring mothers and their babies to school (and its onsite crèche) in the morning and home in the afternoon.

- Door-to-door services to connect older people with important local destinations like supermarkets, doctors’ surgeries, and libraries;

- Formal and informal shared mobility within whānau, hapū, and iwi to support to access important locations like marae, attend events like tangi or wānganga, or transport tamariki to and from kōhanga reo or kura.

- Workplaces that provide all-hours transport for shift workers.

Expanding the range and reach of community transport schemes like these has significant potential to improve equity and respond to unmet transport need in diverse communities, yet they are largely absent from transport policy discussions. Indeed, those who operate these services probably don’t often think of themselves as providing a transport service either.

Community transport solutions need to be part of the decarbonisation strategy for urban transport. At scale, operating frequently and achieving wide coverage, they have the potential to significantly reduce the need for individual car ownership within a diverse range of communities.

Ramping up the provision of low-carbon, shared community transport to the extent that it could start to influence VKT will require much greater collaboration than currently exists between communities, transport agencies, and local and central government. We need to know where community vans and shared vehicles already exist, how they are used, and what kind of support they need, and then start to provide that support. This could include direct funding, but also things like streamlined procurement of vehicles, assistance with the costs of insurance and maintenance, and recruitment and support for volunteer drivers.

Women

At a broad level, men and women have different travel patterns. In general, men tend to travel more, take more and longer work trips, and travel more at peak times. By contrast, women travel more at off-peak times, use cheaper transport modes, take more trips with multiple destinations strung together (known as ‘trip-chaining’), and are less likely to have access to a car. Women are also more likely than men to take frequent trips over short distances for social or recreational purposes.

This is important, because by and large, our transport system – from its embedded assumption that cars will be the primary mode, to public transport designed to move large numbers into urban centres at peak times, to narrow cycle lanes designed for medium distance commuter cyclists – has been designed with men’s travel patterns in mind.

This creates gender disparity in the experience of transport disadvantage and barriers to mobility. Internationally, women are more likely to experience transport-related social disadvantage from missing out on opportunities to participate in society due to a lack of transport options (this may be especially true of sole parents, who are predominantly women, because of both the cost and complexity of trip patterns with children). They are also much more likely to experience the threat of harassment or violence in public spaces, to report feeling unsafe using or waiting for public transport or in taxis or ride shares, less likely to travel alone, and more likely to report stress or anxiety from the logistics and planning involved accessing important destinations while managing these risks.

These international trends are reflected in Aotearoa New Zealand, where women travel less distance overall by car than men, and are more likely to be passengers than drivers. They travel greater distances by public transport than men, despite the fact that public transport services tend not to be well-matched to their transport needs. They walk greater distances than men, but are much less likely to cycle.

A recent study of attitudes to cycling for Māori and non-Māori women in one city found that safety was a major barrier, with participants identifying “a triple burden” of perceived traffic danger, personal safety as women, and the need to be safety-conscious because of their responsibilities for others making them less likely to cycle.10 Gendered differences in active transport start young, with girls less likely than boys to be allowed to travel independently to school, and considerably less likely to cycle, often citing reasons of school uniform.

Women are more likely than men to forgo a doctor’s visit for transport reasons, with young Māori and Pacific women most likely to be affected.

While most gender-related transport disadvantage is experienced by women and minority genders, there are also negative implications for men, namely in road deaths and injuries. Men are more likely than women to be killed or injured on the roads and have a higher hospitalisation rate for traffic injuries across all transport modes.

Takatāpui, queer, and LGBTQI+ people

There is a lack of detailed and specific research about the transport experiences of the queer community both here and overseas, but there is emerging evidence to suggest that they also face considerable transport-related inequity, disadvantage, and poverty.

Like women, takatāpui and queer people may face heightened risks of bullying, harassment, threatening behaviour, and physical or sexual assault in public spaces, including while using or waiting for public transport. In the ‘Counting Ourselves’ survey of more than 1000 transgender and nonbinary people in Aotearoa New Zealand in 2019, 18 percent reported avoiding public transport or taxis due to fear of being mistreated. Such fears are well-founded: reflecting on their experiences of using public transport or taxis, 9 percent of respondents reported being treated unfairly, 15 percent reported being verbally harassed, and 2 percent reported having been physically attacked.11 Fixing this problem is not simply a matter of reducing the incidence of harassment or violence in public spaces; as Kiri Crossland points out in a paper on queer urban planning, truly public spaces must also be actively welcoming to people who are not straight men.12

Because of the discrimination they can face in wider society, transgender and nonbinary people are more likely be unemployed and/or live on very low incomes. In a US study, transgender and gender non-conforming participants reported low incomes and either a lack of employment opportunities, or precarious casual employment that did not conform to peak commuter times. The low-income areas where they could afford to live tended not to be well-served by public transport (an international phenomenon that is replicated here, especially in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland), and they reported infrequent services and long wait times which heightened their vulnerability to harassment and abuse. In Aotearoa New Zealand too, respondents to the ‘Counting Ourselves’ survey of transgender and nonbinary people reported an income approximately half that of an average New Zealander. This means transgender and nonbinary people (and others from the LGBTQI+ community) are more likely to experience transport poverty and disadvantage. In the ‘Counting Ourselves’ survey, 77 percent said they had done without, or cut back on trips to the shops or other local places.13

Pacific people and other ethnic minorities

Globally, ethnic minority groups are more likely to experience transport inequity due to a combination of lower-than-average income, being more likely to live in outer suburbs that are not well-served by public transport, and having greater exposure to safety risks like harassment, air pollution, and traffic accidents (especially as pedestrians since they are less likely to own a car).

Pacific people in Aotearoa New Zealand experience many of these things, but with particular characteristics that are worth noting. Like Māori, Pacific people are much more likely than other ethnicities to go without visiting a doctor for transport reasons, and this contributes to wider well-documented health disparities. Recent analysis of transport patterns and contributions to climate emissions between different ethnic groups is revealing important findings about Pacific people’s mobility. Pacific people travel the shortest distances of any ethnicity across all transport modes, own the fewest cars, and contribute the least of any ethnic group to carbon emissions, by approximately one-third.14 This means it will be particularly important to ensure our efforts to decarbonise the transport system do not negatively impact Pacific people.

Specific research about transport inequity for ethnic minorities in Aotearoa New Zealand more generally is patchy, but it supports the conclusion that they are more likely to experience low income and the transport disadvantage and poverty that comes along with this. Asian women are amongst those more likely to report missing a GP visit for transport reasons, for example. It is likely that difficulties with accessing timetable and ticketing information or communicating with drivers in English as a second language is a barrier to mobility for some people from ethnic minorities, particularly new migrants.

A 2016 issues paper noted that in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, a high proportion of young people from ethnic minority and migrant backgrounds are enrolled in tertiary education in the central city and elsewhere.15 Their transport needs are primarily to access education and part-time jobs, but there has been little research undertaken into how well Auckland’s transport system enables them to do this.

We don’t have good data about how trip patterns vary between ethnic groups, nor how well members of ethnic minorities feel they are served by the current transport system. It is likely that there is considerable unmet need amongst these groups, and considerable variability between them, but with current data currently it is not possible to get a clear picture of the extent of unmet transport need amongst ethnic minority and new migrant communities.

Why a fairer transport system is better for everyone

As we have illustrated, there are major issues of equity and fairness in Aotearoa New Zealand’s current transport system. There are many reasons to pursue transport equity (when the benefits and costs of transport policies and projects are fairly distributed), transport justice (when decision-making processes are fair, representative, and ensure the transport system meets the basic needs of everyone), and mobility justice (when unjust power relations and uneven mobility are fully addressed). Achieving an equitable transport system will benefit everyone.

Basic fairness and human rights

Few would contest the statement that everybody should be able to get where they need to go affordably, accessibly, and in good time. Being able to do so is a necessary precondition to accessing employment, education, social, and cultural opportunities. Yet as long as transport planners and decision-makers keep resourcing a transport system that restricts mobility for some while enabling it for others, we will never enjoy equality of opportunity in Aotearoa New Zealand.

This affects us all. At different times in our lives, we all experience some barriers to mobility. Often, this happens suddenly via a change of circumstances such as the birth of a child, the onset of an illness or impairment, loss of employment, or the ageing process. Such rapid loss of mobility can leave us isolated and vulnerable and can hinder recovery by making it harder to find work, see friends and family, or access recreation. In an equitable transport system, a change in circumstances would not necessarily entail a loss of mobility, and those with permanent impairments and restrictions would also enjoy full mobility. As noted by Erin Gough on page 19, the fact that Aotearoa New Zealand does not currently provide equal access to the transport system puts us in breach of our international human rights obligations.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

It also puts the Crown in breach of its Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations. The fact that Māori are more likely to have low incomes, experience disability, have chronic health conditions, be killed or injured on the road, find themselves on a path to the criminal justice system via minor traffic offences, and experience transport disadvantage and poverty are the legacy of discriminatory colonial policies over many decades.

When it was signed in 1840, Te Tiriti promised Māori tino rangatiratanga and equal citizenship, but it was consistently breached by the Crown in the way the country was settled and governed. Today, it creates obligations on the Crown to ensure public services (including the transport system) recognise Māori as tangata whenua, partner with hapū and iwi to deliver equitable outcomes for Māori, and share power and resources to enable ‘by Māori for Māori’ solutions and the exercise of tino rangatiratanga.

In transport, this could look like mandating Māori representation on transport decision-making bodies, handing authority to iwi and hapū to manage aspects of the transport system in their rohe, partnering with Māori to develop specific plans to improve transport outcomes for Māori, and supporting hapū, iwi, and kaupapa Māori organisations with the resources they need to play a larger part in transport decision-making and governance.

Opportunity cost

At present, there is a considerable opportunity cost from all the restricted mobility our inequitable transport system produces. It is difficult to quantify, because we don’t have good data about the full extent of forgone trips, unmet transport need, or repressed demand, but it is reasonable to assume that if the transport system prioritised equity, there would be widespread benefits, not only for those directly affected, but for our economy and society as a whole. These benefits could include:

- More people accessing primary healthcare, reducing the demand for (and costs of) urgent care and hospitalisations when untreated conditions become critical.

- Fewer people injured or killed on the roads (especially the disproportionate trauma experienced by Māori), producing cost savings for the ACC and health systems and preventing grief, stress, and lost income for many families.