About the Helen Clark Foundation

The Helen Clark Foundation is an independent public policy think tank based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, at the Auckland University of Technology. It is funded by members and donations. We advocate for ideas and encourage debate; we do not campaign for political parties or candidates. Launched in March 2019, the Foundation issues research and discussion papers on a broad range of economic, social, and environmental issues.

Our philosophy

New problems confront our society and our environment, both in New Zealand and internationally. Unacceptable levels of inequality persist. Women’s interests remain underrepresented. Through new technology we are more connected than ever, yet loneliness is increasing, and civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite greater awareness. We aim to address these issues in a manner consistent with the values of former New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark, who serves as our patron.

Our purpose

The Foundation publishes research that aims to contribute to a more just, sustainable, and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. We welcome your support: please see our website www.helenclark.foundation for more information about getting involved.

About WSP in New Zealand

As one of the world’s leading professional services firms, WSP provides strategic advisory, planning, design, engineering, and environmental solutions to public and private sector organisations, as well as offering project delivery and strategic advisory services. Our experts in Aotearoa New Zealand include advisory, planning, architecture, design, engineering, scientists, and environmental specialists. Leveraging our Future Ready® planning and design methodology, WSP use an evidence-based approach to helping clients see the future more clearly so we can take meaningful action and design for it today. With approximately 50,000 talented people globally, including 2,000 in Aotearoa New Zealand located across 40 regional offices, we are uniquely positioned to deliver future ready solutions, wherever our clients need us. See our website at wsp.com/nz.

About the Post-Pandemic Futures Series

The world has changed around us, and as we work to rebuild our society and economy, we need a bold new direction for Aotearoa New Zealand. A new direction that builds a truly resilient economy and a fair labour market. A new direction that embraces environmental sustainability and provides for a just transition. A new direction that nurtures an independent and vibrant Kiwi cultural and media landscape. And a new direction that focuses on the wellbeing of all in society.

To get there, we need to shine a light on new ideas, new policies, and new ways of doing things. And we need vigorous and constructive debate. At the Helen Clark Foundation, we will do what we can to contribute with our series on Aotearoa New Zealand’s post-pandemic future. This is the fifth and final report in a series discussing policy challenges facing New Zealand due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the fourth report in our partnership with WSP New Zealand.

Whakataukī

Hokia ki ō maunga kia purea ai koe e ngā hau a Tāwhirimātea.1

He mihi: Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following people and organisations who have assisted with this work. Ngā mihi nui.

WSP New Zealand for their ongoing support of the Helen Clark Foundation and my research, especially David Kidd, Bridget McFlinn, Kate Palmer, and Nic Scrivin.

Professor Paul Spoonley for contributing a Q&A on New Zealand’s migration and demographic trends, and for expert peer review and guidance.

Lamia Imam for contributing a Q&A about her experience returning to New Zealand.

Kea New Zealand, especially Toni Truslove and Ele Quigan, for sharing insights and expertise and for their peer review.

MBIE for sharing provisional results of the Survey of New Zealand Arrivals.

Tracey Lee for her 2013 ‘Welcome Home’ thesis on the experiences of returning New Zealanders and for sharing a range of useful resources, references, and perspectives (also for not minding that I borrowed her thesis title!)

Peter Wilson and Julie Fry for sharing feedback and advice, and Julie for a thought-provoking conversation from MIQ.

Melanie Feisst for sharing useful resources and references from afar.

My colleagues at the Helen Clark Foundation Kathy Errington, Paul Smith, Matt Shand, and Sarah Paterson-Hamlin.

Glossary of te reo Māori terms2

Nau mai: Welcome!

Whānau: Extended family, family group – the primary economic unit of traditional Māori society.

Hapū: Kinship group, clan, tribe, subtribe – section of a large kinship group and the primary political unit in traditional Māori society. A number of whānau sharing descent from a common ancestor, usually being named after the ancestor, but sometimes from an important event in the group’s history.

Iwi: Extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people, nationality, race – often refers to a large group of people descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory.

Whakapapa: Genealogy, genealogical table, lineage, descent – reciting whakapapa was, and is, an important skill and reflected the importance of genealogies in Māori society in terms of leadership, land and fishing rights, kinship and status. It is central to all Māori institutions.

Haukāinga: Home, true home, local people of a marae, home people.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi: The Treaty of Waitangi (Māori version).

Te Ao Māori: The Māori world.

Tikanga: Correct procedure, custom, habit, lore, practice, convention, protocol – the customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Tangata whenua: Local people, hosts, indigenous people – people born of the whenua, i.e. of the placenta and of the land where the people’s ancestors have lived and where their placenta are buried.

Tangata tiriti: ‘Treaty people’ or New Zealanders of non-Māori origin.

Tauiwi: Non-Māori.

Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship, stewardship.

Tīpuna: Ancestors.

Executive Summary

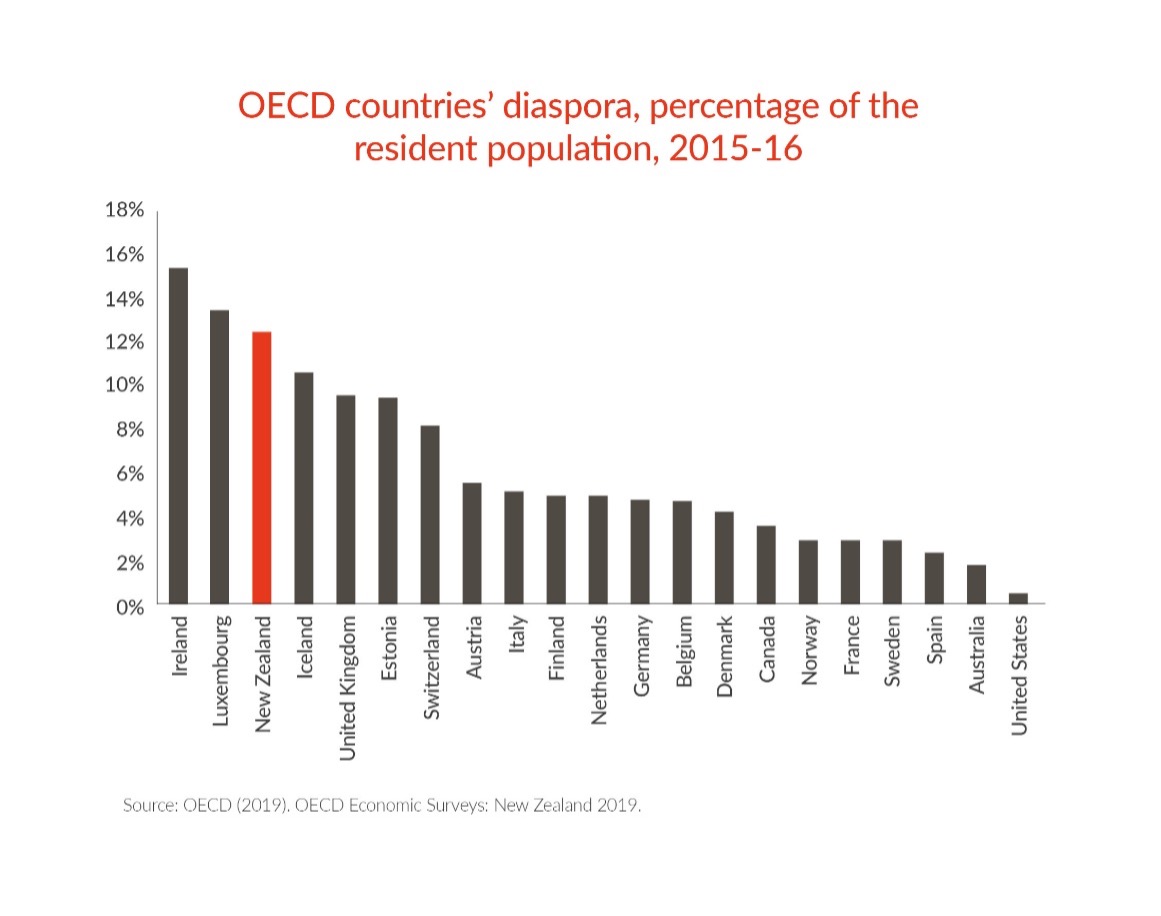

Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the largest per-capita diasporas of any OECD country. In 2015-16, our diaspora – defined as the dispersed population of people who live away from their original geographical homeland – was the third largest in the OECD,3 and estimates suggest there could be as many as one million New Zealand citizens and their children living in other countries.4 New Zealanders living overseas live mostly in Australia and other English-speaking countries, tend to by highly educated, and have the potential to bring considerable benefits to Aotearoa, not only by returning to live, but also by maintaining strong economic, social, and cultural connections to home.

Before 2020, for at least twenty years, there had been a net loss of New Zealand citizens every year. We frequently lamented this as a ‘brain drain,’ and successive governments sought ways to attract New Zealanders home, from the ‘Catching the Knowledge Wave’ conference in 2001, to the late Sir Paul Callaghan’s memorable desire to make New Zealand “a place where talent wants to live”. Governments from both sides of the political spectrum recognised that retaining and attracting back talented and highly skilled New Zealanders can contribute to economic growth, creative innovation, cultural diversity, and social wellbeing, and strengthen international networks and connections, but translating this recognition into a strategic policy approach to our diaspora has proved challenging.

Less discussed, but is equally important, is the potential benefit of encouraging New Zealanders who remain overseas to maintain strong social, cultural, and economic connections to their homeland. This may be particularly important for Māori – to retain connection to whānau, hapū, iwi, and whakapapa – no matter where they are in the world. There is also good evidence that maintaining strong links with overseas nationals has economic benefits for the home country.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided Aotearoa New Zealand with an opportunity to rewrite the story of our diaspora.

Early in the pandemic there was speculation that an unprecedented influx of New Zealanders would return, and indeed some have. Many people will know someone who has returned from overseas since the start of the pandemic, some traumatised by what they have lived through in places with high infection and death rates. Yet the narrative of New Zealanders returning in droves during the pandemic is not (yet) supported by the evidence.

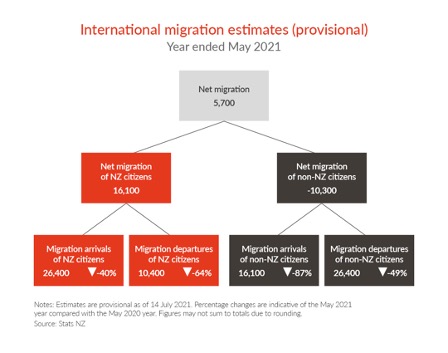

Net migration of New Zealand citizens has been positive during the pandemic, but mainly because the number of arrivals fell less than the number of departures. In the year from May 2020 to May 2021, 26,400 New Zealand citizens arrived in the country, down 40% on the previous year. In the same period, 10,400 New Zealand citizens departed, down 64%, leaving a net gain of 16,100 New Zealand citizens. When offset by arrivals and departures of non-New Zealand citizens, which were also drastically down, there was a small net migration gain of 5,700 in the year to May 2021.5 The year from March 2020 to March 2021 represented the largest ever annual drop in net migration.6

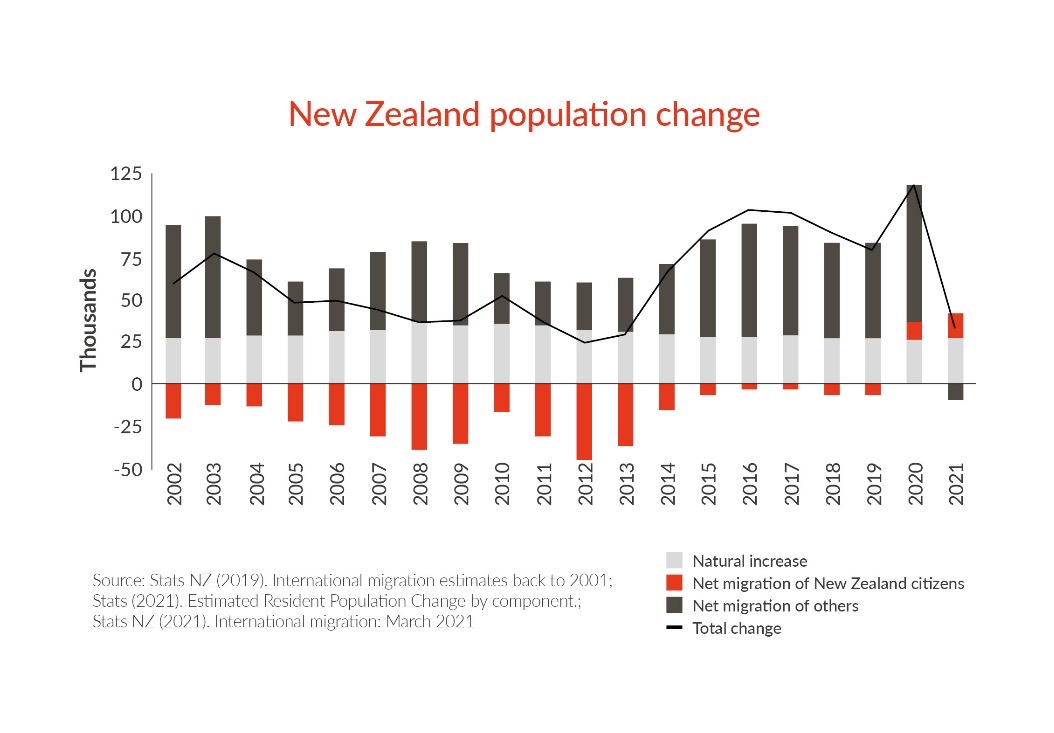

While small in number, this net gain in New Zealand citizens may represent the start of a new trend. Prior to December 2019, New Zealand had not experienced a net gain in New Zealand citizens for at least twenty years. That trend had begun to turn around just before COVID-19 and its border closures and lockdowns hit.

Now, many more New Zealanders who are currently overseas may be preparing to return home. According to expat organisation Kea’s 2021 ‘Future Aspirations’ survey of offshore New Zealanders, 31% were planning to return, with more than half of those planning to arrive within the next two years. 43% of those intending to return stated that COVID-19 was a key factor in their decision and 23% specifically cited the New Zealand Government’s response to the pandemic.7

This presents a significant opportunity to New Zealand. While it is not possible to extrapolate from intention survey data to give a precise prediction of potential returnees (partly because no government agency maintains an official measure of the total number of New Zealanders living overseas), many tens of thousands could return in the next few years. On average, these people are likely to be highly educated and highly skilled and have the potential to contribute significantly to our economy and productivity.

We know something about those who have already returned during the pandemic thanks to the Government’s Survey of New Zealand Arrivals, which asks people arriving about their connections, intentions, employment, and family situations.

Provisional results for those surveyed between August 2020 and January 2021 were released in June 2021. Respondents to the arrivals survey were highly educated: 61% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Since they had arrived, 37% had found a job here, 13% were working remotely in an overseas job, 10% had returned to a job they already held here, and 35% were not in paid work. Significantly, 24% said they would leave New Zealand again if the global COVID-19 situation improved – meaning there is an important opportunity and challenge to retain them, if we decide this is a priority.

Of course, there will always be some New Zealanders living overseas, especially as international borders begin to reopen and we start to transition towards a post-pandemic future. This also presents an opportunity to start thinking of our large per-capita diaspora not as a ‘drain’ but as a potential source of economic, cultural, and social exchange.

This means developing a better understanding of who is in the New Zealand diaspora, where they live, what their goals, aspirations, and connections to New Zealand are, and how we can build on these connections to benefit both members of the diaspora and New Zealand as a whole.

It means considering cultural factors such as what it means for Māori to live away from (and return to) their haukāinga, and how welcome returning New Zealanders feel when they do come home.

And it requires preparing our infrastructure to meet the needs and expectations of everyone who will live here in the future, such as investing in world-class, sustainable cities and towns; ensuring affordable, accessible and high-quality housing for all, and making sure incomes keep pace with the cost of living.

It is also essential to consider how our policy response to all of these issues can uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi.

This report canvasses these issues and considers how Aotearoa New Zealand can strengthen connections with our large diaspora, remove barriers to their return, and prepare our cities and towns for the demographic trends of the post-pandemic future.

It consists of three parts. In Part 1, ‘The new Aotearoa’ we examine current demographic trends, looking at emerging issues prior to the pandemic, and the immediate impact of COVID-19 and the border closure. This part features a Q&A with Distinguished Professor Paul Spoonley of Massey University.

In Part 2, ‘The team of six million’, we consider the estimated one million New Zealanders and their children living overseas, those who have recently returned to live, and those who may be planning to come home soon, and make the case for a more purposeful approach to managing New Zealand’s diaspora. This part features a Q&A with Lamia Imam, who returned home to Aotearoa from the US in 2020, as well as insights from recent surveys conducted by Kea and the Government.

In Part 3, ‘Ready for the future’, we consider how we can prepare to meet both the needs of a growing, diversifying, ageing, and urbanising population, and the expectations of the diaspora, with a particular focus on how we can ensure our cities and towns are world-class and globally competitive. This part features an insert from our partners WSP New Zealand based on their recent report about the 20-minute cities movement and its potential application here.

After considering these issues, we have identified three planks that should underpin an effective policy response to meet the expectations of the kiwi diaspora and prepare for the potential trends of the post-pandemic future. These are:

- Understand and tap into the potential of the offshore diaspora

- Roll out the welcome mat to those who wish to return

- Develop world-class cities and towns where people want to live

We make policy recommendations under each of these headings.

Summary of Recommendations

1. Understand and tap into the potential of the offshore diaspora

We recommend that the government:

- Develop an Aotearoa New Zealand Diaspora Strategy, and create a ministerial portfolio with responsibility for ensuring its implementation. As part of this strategy:

- Obtain a robust, accurate, and regularly updated measure of the number of New Zealanders living overseas and their whereabouts;

- Strengthen current efforts to tap into diaspora networks to achieve New Zealand’s trade and enterprise goals;

- Ensure the diaspora strategy meets Crown obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. As a starting point, any strategy should understand the cultural implications for Māori living overseas, support international Māori organisations, and facilitate opportunities for the Māori diaspora to connect to whānau, hapū and iwi and access te reo and tikanga Māori. This list is not definitive, and the full strategy should be developed in partnership with Māori.

- Adopt the Electoral Commission’s recommendation to amend the Electoral Act to ensure overseas voters who have been unable to visit New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic (and therefore risk losing their eligibility for electoral enrolment) are not prevented from voting in upcoming local and general elections.

2. Roll out the welcome mat to those who wish to return

We recommend that the government:

- Develop a reintegration and resettlement strategy for returning New Zealanders, including the provision of information and advice about:

- Employment opportunities;

- Portability of overseas qualifications;

- Taxation, retirement savings, and portability of overseas pensions;

- Immigration of non-New Zealand citizen partners and children;

- Transitioning children into New Zealand education and childcare settings;

- Accommodation, income, and living expenses.

- Ensure senior government figures publicly endorse and celebrate the contributions, skills, and potential of returning New Zealanders.

3. Develop world-class cities and towns where people want to live

We recommend that the government:

- Implement the recommendations of our previous report, The Shared Path, to accelerate the use of low-traffic neighbourhoods in New Zealand’s cities and towns to reduce emissions, improve road safety, and promote connected communities.

- Support the application of the 20-minute city movement in New Zealand, including by piloting its application in Kāinga Ora-led urban developments.

- As part of the 30-year Infrastructure Strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand:

- Develop a national spatial plan;

- Adopt a systems-thinking approach;

- Ensure Te Tiriti o Waitangi underpins the strategy and is upheld by all central and local government agencies involved in the delivery of infrastructure. This includes, for example, understanding how infrastructure planning and building impacts on Māori rights and interests over land and water, which can only be fully understood when there is meaningful representation from hapū and iwi in infrastructure decision-making.

- Continue efforts to accelerate the building of high-quality, medium-density housing, and consider issuing guidance under the National Policy Statement on Urban Development to ensure densification meets best practice standards of design and accessibility to facilitate community wellbeing.

Expand the government response to the housing affordability crisis to include measures to address both the supply and demand factors driving the crisis.

Part 1: The new Aotearoa

How our demographic profile is changing

Our population has been growing

Prior to COVID-19, New Zealand had been experiencing a period of high population growth – approximately 2% per annum, among the highest in the OECD. Between 2013 and 2020 strong positive net migration accounted for about two-thirds of this growth, with the remaining third from natural increases (births outnumbering deaths). Significantly, we had been experiencing net losses of New Zealand citizens for the last two decades, with peak losses in 2008-9 and 2012-13 associated with the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and its impacts. 2020 and 2021 to date, were the first years in which we experienced a net gain of New Zealand citizens since at least 2002.

New Zealand population change8

We are ageing and diversifying

As well as growing in size, our population has been diversifying and ageing. Stats NZ projects that New Zealand will be significantly more ethnically diverse in 2043 than it was in 2018, due to a combination of slower population growth for the ‘European or Other’ group and high levels of natural increase and/or net migration for other ethnic groups. Both Māori and Asian populations are expected to surpass one million within the next ten years, with Asian communities overtaking Māori as the second-largest ethnic group. The Pacific population will pass 500,000, and the ‘Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African’ and Indian groups will be the fastest growing categories.9 All ethnic populations will have a greater proportion of their population in the 65+ age group by 2043 due to a combination of declining fertility and people living longer, but the future cohort of children and young people aged 0-14 in 2043 will be considerably more diverse than it is now. This is because the ‘European or Other’ group will grow more slowly than all other ethnic groups.

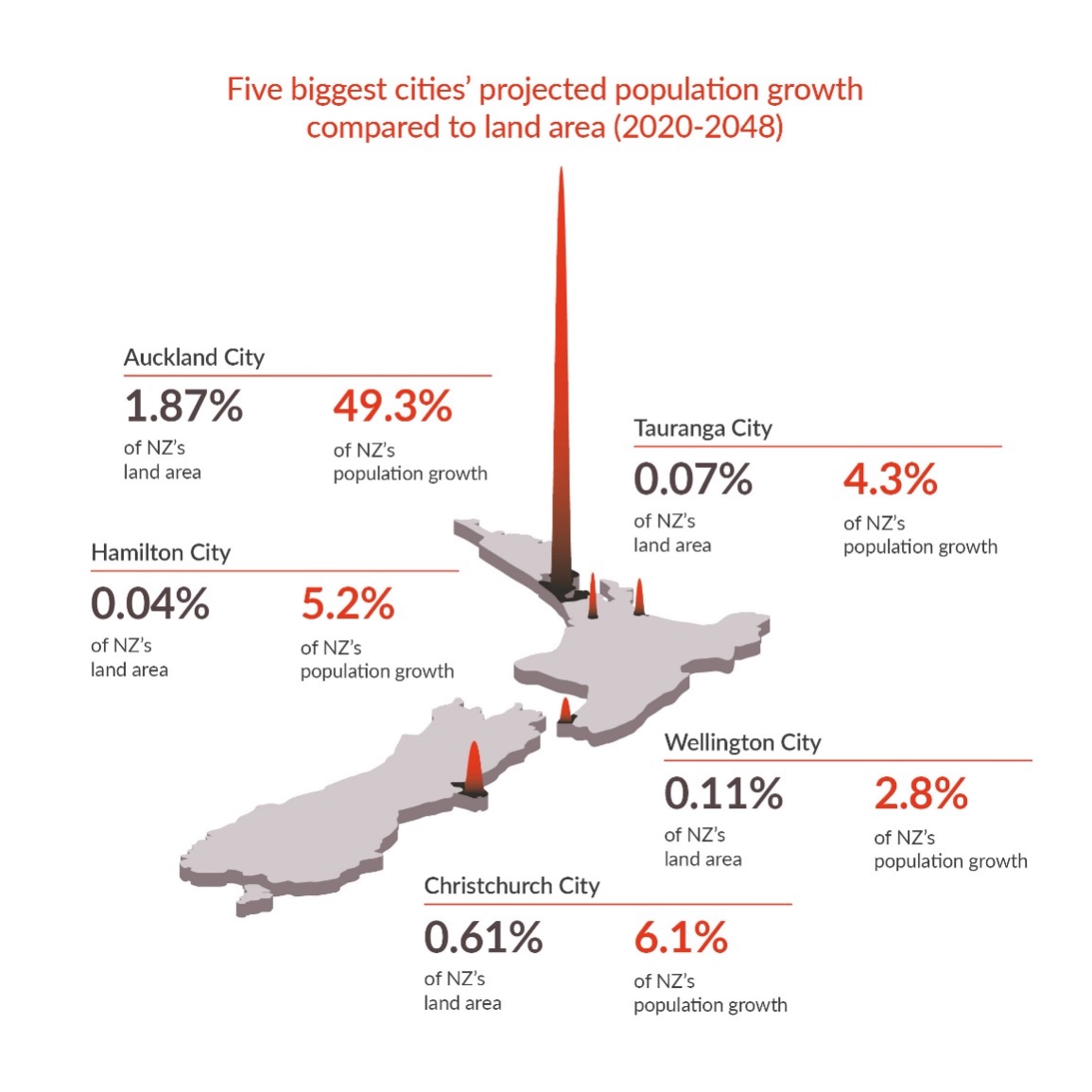

Our cities are growing, especially Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland)

Our population is also urbanising, with nearly three quarters of population growth in the next 30 years projected to take place in cities. Auckland alone will account for half of this growth. Its population is projected to rise from about 1.7 million currently to 2 million by early next decade, and by 2048 it could be home to 37 percent of the total population. Another quarter of the country’s projected growth will be in the other 12 cities, resulting in an estimated 968,000 more city dwellers in 2048 than in 2018.

Five biggest cities’ projected population growth compared to land area (2020-2048)10

As the Infrastructure Commission has noted, this growth places increasing pressure on existing urban infrastructure, and creates demand for new infrastructure, especially in Auckland. In particular, the Commission notes the need for more affordable and abundant housing that improves social, economic, and health outcomes and urban environments that provide greater connectivity with employment, social services and recreation opportunities.

It also notes that population growth in our cities creates opportunities as well as challenges: “While population growth may place further strains on infrastructure, if managed properly it could make services such as public transport, water services, and wastewater treatment plants more affordable as the costs are spread across more users. Productivity and wages can increase if growth is well managed in our cities.”11

Some regions will grow rapidly, while others will stagnate or decline

In the coming decades, New Zealand’s population is expected to concentrate more and more in Auckland and the top half of the North Island – outside of Auckland, the population is predicted to grow rapidly in the Waikato, Bay of Plenty, and Northland regions. This will create an uneven set of challenges for the regions. For some, it will result in similar growth challenges, as the Infrastructure Commission has noted: “if our cities fail to meet the challenges of growth, people will look to the regions as alternatives. This could result in a ripple effect, with the problems of growth simply being transferred to regional New Zealand.”12

On the other hand, in other parts of the country, particularly rural parts of the South Island, the challenge could be population stagnation or even decline. Stats NZ currently predicts six districts to have smaller populations in 2048 than in 2018; these are the Waitomo, Ruapehu, Buller, Grey, Westland, and Gore districts.13 Many other regions and districts are likely to experience only very small population growth, and primarily in the 65+ age group, in that time.14

This challenge to the regions requires careful management, because, as the Infrastructure Commission notes, the regions are still “the economic backbone from which the bulk of our primary exports are sourced.”15

COVID-19 has had an immediate and significant impact

When we closed our border at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, arrivals of new migrants immediately ceased, as did – to a large extent – migrant arrivals of New Zealand citizens. In the year from May 2020 to May 2021, there was an 87% drop in migrant arrivals of non-New Zealand citizens, and a 40% drop in migrant arrivals of New Zealand citizens.16 The year from March 2020 to March 2021 represented the largest ever annual drop in net migration.17

These figures do not (yet) support the narrative of New Zealanders returning home in droves from overseas. Half as many New Zealanders returned during 2020 as we might expect in a normal year, but because very few departed, this still resulted in a net gain. As Distinguished Professor Paul Spoonley puts it in his Q&A later in this report, we experienced a ‘brain retention’ rather than a ‘brain gain’.

However, this small net gain could indicate the start of a new trend. If the intentions of overseas New Zealanders indicated in recent surveys are predictive of future trends, we could expect a large number of New Zealanders to return to live in the coming months and years. We will address this possibility in more detail in Part 2.

It is difficult to predict the impact that COVID-19 will have on our population trends long-term. Stats NZ takes what it deems to be the most likely impact into account in its long-term projections and assumes that net migration will fluctuate around an average gain of 25,000 per annum in the coming years (much lower than the peak of almost 80,000 just before the pandemic). However, it is very difficult to predict the ongoing impact of the pandemic, including how long our borders will remain closed, whether we will continue to enjoy COVID-free status, the difficulties of establishing and maintaining travel bubbles with other countries in the face of new outbreaks, and how the vaccine rollout in other countries will impact on economic and migration trends. Furthermore, these projections assume current policy settings, and do not try to anticipate future major policy changes which may affect population change, yet New Zealand’s immigration policy settings are under active review.18

As best we can predict in a very unpredictable world, the most likely scenario for Aotearoa New Zealand in coming decades is that our population will continue to grow, diversify, age, and urbanise, but perhaps at slightly lower annual growth rates and with a smaller contribution from net migration. It is possible that increased return migration from overseas New Zealanders may offset some of the effect of reduced international migration. In the next Part, we consider the needs, experiences, and potential contribution of the estimated one million overseas New Zealanders and their children to our post-pandemic future.

Should we plan our population change more purposefully?

One complicating factor for understanding future population trends is the both the volatility of New Zealand’s past population growth, and the challenge of accurately projecting it in future.

Population projections have both over-shot and under-shot growth in past decades.19 This presents a challenge for planners and decision-makers, who need to be familiar with the risks of uncertain future projections when planning new infrastructure, economic policies, and social supports. Current best practice is to present, ‘high’ and ‘low’ growth scenarios as well as planning for the growth scenario that is ‘most likely’.

One option to smooth volatility in population growth and projections is to adopt a national population strategy that sets out a preferred long-run population path. This is the approach taken by Australia in its population strategy, released in 2019, which aims to support economic growth, reduce population pressures in major cities, and support regions to attract the people they need.20

The case for such a strategy is that by setting a preferred population path (whether for growth or stabilisation), and adopting policies designed to achieve it, Aotearoa New Zealand can plan future infrastructure, economic, and social policy more accurately to meet future challenges, and manage both the benefits and risks of a growing population more carefully. Our partners at WSP favour this approach.

Population policies, though, are controversial. High population growth brings environmental pressure, and is likely to be unpopular in the current context of concern about climate change. Rapid population growth via migration can also rapidly shift the cultural make-up of a society, and if not managed sensitively, can threaten social cohesion. On the other hand, policy that aims to limit migration risks fanning the flames of racism and xenophobia, and policies that seek to influence the fertility rate can be seen as interfering with individual and family choices. For all these reasons, successive governments have steered clear of adopting purposeful population strategies.

One thing is certain: our population will change, and the policies we choose, like immigration settings and the supports available to families, will in part determine what this change looks like. Whether we do this as part of a concerted strategy with a preferred pathway in mind, or allow it to unfold more organically, there will be significant infrastructure and policy implications.

Q&A with Distinguished Professor Paul Spoonley

Distinguished Professor Paul Spoonley is an Honorary Research Associate and former Pro-Vice Chancellor at Te Kura Pukenga Tangata (College of Humanities and Social Sciences) at Massey University. He is the author or editor of 28 books, including The New New Zealand: Facing Demographic Disruption (Massey University Press, 2020, 2021). His research interests include social cohesion, racism, Pākehā identity, demographic change, the far right, white supremacism and anti-Semitism, immigration policy and settlement, diversity impacts and recognition, and the changing nature of work.

In broad terms, what were Aotearoa New Zealand’s long-term migration trends like before COVID-19, and what pressure points or issues did these trends create for our domestic policy settings?

The last ten years have provided a very interesting migration trajectory. It begins in the period 2011-13, towards the end of the GFC, when large numbers of New Zealand citizens and permanent residents departed to live elsewhere, especially Australia – 53,800 in 2012 alone. In 2013, this trend began to reverse and the numbers continued to climb, reaching a peak in 2017 before the Labour Government reduced the numbers approved for residence. However, the number grew again in 2019, and reached a peak in mid-2020. The numbers for the 12 months to June 2020 indicate a net gain of more than 79,000 people, the highest net gain in permanent and long-term migrants ever – and that included three months of lock-down! But there is a parallel story – the doubling of those on temporary visas. At the start of lockdown in March 2020, there were 221,298 people in New Zealand on short term work visas and another 81,999 on study visas.

These arrivals, both temporary and permanent, had two primary impacts. The first is that by 2020, many sectors, employers, and organisations had come to rely on migrant labour, both seasonal and permanent. In some sectors, migrant workers were up to 80% of the workforce (pickers on orchards for example, although New Zealand workers still dominated the processing of these same crops). In other sectors such as eldercare, IT, or health, migrant workers ranged from a quarter to a half of the workforce. The second is that this high net migration contributed to faster than projected population growth (around 2% p.a, which is high for an OECD country in recent years). Two-thirds of this growth was due to net migration, and this was putting additional pressure on infrastructure provision and the housing market. COVID-19 has stopped these trends in their tracks, and the biggest impact has been on labour supply.

New Zealand has one of the largest international diasporas of any OECD nation, with approximately one million New Zealanders living overseas. Do we know much about them?

This reflects an important rite of passage of New Zealanders, the ‘OE’ [Overseas Experience]. People started spending more time overseas in the 1970s and ‘80s, especially as New Zealand now shared a common labour market with Australia. For a long time, New Zealanders provided a lot of the lower skilled labour for the Australian economy. But the Australians started to change their policy settings from 2001 to avoid ‘dole bludgers’ from New Zealand and in response to a perception that New Zealand provided a back door for Pasifika migrants. The diaspora was then made larger by events during the GFC. New Zealand now has the third largest proportional diaspora in the OECD, behind those of Luxembourg and Ireland. This would not be the issue it is if successive New Zealand governments had invested in a diaspora management strategy to maintain connectivity with and utilise the experiences and skills of the diaspora. There was a moment after the ‘Knowledge Wave’ conference in 2001 when this seemed possible, but it has not lasted.

We’ve heard a lot of anecdotal data about large numbers of New Zealand citizens returning to live as a response to COVID-19. Is this trend borne out by the data that is emerging? Do you think we can expect to see more returning New Zealanders in the coming months and years?

This is one of those urban myths about migration that has been fed by the media. If you compare the number of returning New Zealanders (who qualify as migrants because they have been outside New Zealand for 12 months or more) for the year up to March 2020 and then again for March 2021, there is a drop of almost 50% in those migrating (returning) to New Zealand. But there is also a net gain of New Zealanders of about 15,000 which contrasts markedly with the normal story of net annual losses of New Zealanders. The gain comes from the fact that many fewer New Zealanders (down 80%) are leaving to live long term overseas. This means that we have ‘brain retention’ rather than a ‘brain gain’. To date, there are many fewer New Zealanders returning than you would normally expect, but it has become an important story because of the net gain as many more are unable to leave.

There’s also a lot of talk about attracting back ‘high skilled’ New Zealanders – but every citizen has the right to return regardless of their level of education or earning power. Are we likely to see an increase in returning citizens, and how can we prepare for this eventuality?

There is one aspect of the New Zealand migration management system that cannot be managed: the departure and return migration of New Zealanders. Coincidently, we also have not collected data on these migrants until recently. We know a lot about other migrants as part of their visa application and approval process, but this does not apply to New Zealand citizens. Whatever targets we set for residence approvals, they will not apply to New Zealanders. And the migration churn of New Zealanders can’t be managed in the way that other migrant flows can. In nearly any given year, New Zealand migrant arrivals still constitute the largest group of arrivals. They also dominate, by a long way, departures. What, therefore, would incentivise these diaspora New Zealand communities to consider coming back to New Zealand? It is a very difficult question to answer.

We have an opportunity right now with the border mostly closed to redesign our policy settings. If you had a magic wand, what changes would you make now to ready us for when international borders re-open after the pandemic?

I would like to see us explore a pathway to permanent residence for those migrants on temporary visas who have been here since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and who meet the good character and labour market tests. I would establish more robust labour market conditions to ensure that migrant labour is not substituting for local labour, and which might be suppressing local wages. This should be done at an industry level otherwise every employer is going to argue that they have a need which is a priority. I would establish a system like the Provincial Nominee Programme in Canada where regions get to identify local labour shortages and to allocate some of the points that are required for visa approval. Our system is a national system, which benefits Auckland significantly but not many regions. There should be a much more explicit regional dimension; but the regions are often at fault here as they do not have clear processes for identifying labour shortages (unless there is a crisis) or are not always prepared to invest in attracting and helping to settle immigrants. I certainly think we do need to invest in a diaspora management policy that makes a virtue out of the country’s diaspora and which looks to attract back skilled, experienced New Zealanders – and to welcome them when they do come back. And then there are humanitarian elements, everything from increasing our very inadequate number of refugee approvals, through to ensuring appropriate family reunification options and maintaining programmes such as the RSE [Recognised Seasonal Employer] scheme that is of such benefit to Pacific nations.

Part 2: The ‘team of six million’

During the COVID-19 pandemic we have become accustomed to talking about New Zealand’s ‘team of five million’, but it could be just as accurate to talk about the ‘team of six million’, taking into account the up to one million New Zealanders and their children who currently live overseas.21 Most New Zealanders will have family or close friends living overseas, especially in Australia.22 In this part we consider these New Zealanders living overseas, as well as those who have recently returned to live, and those who may be planning to come home soon. What do we know about the New Zealand diaspora? How likely are they to return in large numbers in the coming months and years? What has the experience of returning home during the pandemic been like? We make the case for a more purposeful approach to the relationship with New Zealand’s diaspora.

It is hard to access accurate, up-to-date figures about the number of New Zealanders living overseas, but it is thought that Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the largest total diasporas of any OECD country. In 2015-16 our diaspora was the third largest in the OECD, after Ireland and Luxembourg.

OECD countries’ diaspora, percentage of the resident population, 2015-1623

The estimate of one million New Zealanders and their children overseas is an extrapolation,24 but not an unreasonable one. We know that there are between 570,000 and 600,000 New Zealanders in Australia,25 and this is estimated to constitute about 75% of New Zealand’s total diaspora. This would put the total at around 800,000 but given these estimates do not include children, it is possible and indeed likely that including children, the total number is as high as one million. The fact that we don’t have accurate data though, is an issue that needs addressing.

Defining the ‘diaspora’

A diaspora is a dispersed population of people who live away from their original geographical homeland. There are different reasons why a population might be dispersed in this way. Historically, the term was used to describe the forced dispersion of populations from their homelands. More recently, it has been used to describe any group of people who identify with a ‘homeland’ or home country, but live away from it, including for reasons of work or trade. The New Zealand diaspora is cited as an example of a ‘gold collar’ diaspora, characterised by the emigration of citizens who are in a position to choose where they migrate to, are in demand for their skills, and are highly mobile.26

The historical context is worth bearing in mind when we talk about the New Zealand diaspora. Māori, as tangata whenua, are the only population who can claim Aotearoa as their traditional, geographical homeland. Most New Zealanders are tauiwi/tangata Tiriti, whether recently arrived, or descended from migrant families going back several generations. For historical and cultural reasons, it can mean something different – and have a different impact – for Māori to live away from Aotearoa than for tauiwi, and we should be careful about grouping the experiences of all New Zealanders overseas, Māori and non-Māori, into one category.

In terms of defining what constitutes a ‘diaspora’ for policy purposes, there is no formal, internationally-recognised definition. Some countries have adopted official government diaspora strategies, which define the term widely. The Irish diaspora for example, as defined in the Irish Government’s Diaspora Strategy, comprises:

- Irish Citizens living overseas, whether born in Ireland or born overseas to Irish parents;

- The ‘Heritage diaspora’, of people of Irish descent, anywhere in the world;

- The ‘Reverse diaspora’, of people who have lived, worked, or studied in Ireland, then returned home to other countries; and

- The ‘Affinity diaspora’, of people who feel a strong connection to Ireland’s people, places, and culture.27

Clearly, not all of these groups have a right to residence or citizenship in Ireland, but the Irish Government believes all of them have a role to play in supporting the welfare of Irish people at home and abroad, and strengthening economic and cultural ties between Ireland and the global community.

For the purposes of this report, when we talk about the New Zealand diaspora we are talking primarily about New Zealand-born citizens (and sometimes permanent residents) and their children living in countries other than New Zealand. However, it is worth keeping these wider definitions of diaspora in mind when thinking about the potential economic, social, and cultural benefits of forging closer ties with people connected to Aotearoa New Zealand around the globe.

Rights to citizenship, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the Māori diaspora

The ‘Heritage diaspora’ category is interesting to consider from a Te Tiriti o Waitangi perspective. Under current legislation, New Zealand citizens, including Māori, may pass citizenship on to their children born overseas, but not their grandchildren.28 This means there is no automatic right to New Zealand citizenship for subsequent generations of the Māori diaspora, despite the fact that in Te Ao Māori, belonging is a function of whakapapa (broadly defined as genealogy), not place of birth.

This concern is not theoretical. It is estimated that there are almost 200,000 Māori in Australia alone, and the history of Māori migration to Australia stretches back at least 200 years.29 Many whānau Māori in Australia are now in their second or third generation. While under current rules, New Zealanders and Australians can move freely between the two countries and live and work in both, only citizenship confers an automatic right of return if the rules were to change in future. Second and third generation Māori living in countries other than Australia may be even more affected. While it is theoretically possible to maintain New Zealand citizenship by descent if every generation prioritises this, it is likely that in many cases this may have lapsed.

The question of indigeneity and citizenship has recently been tested in the Australian courts, in the Love vs Commonwealth and Thoms vs Commonwealth cases, in which two Aboriginal men, born outside of Australia and therefore not Australian citizens, challenged the Australian Government’s authority to deport them, basing their claim on their Aboriginal heritage.30 In February 2020 the Australian High Court upheld their appeal and ruled they could not be deported, but the question of whether they should be entitled to citizenship remains unresolved.31

In Aotearoa New Zealand, there are Tiriti o Waitangi implications to this question as well. Article Three of Te Tiriti extends to Māori the rights and privileges of British citizenship; as citizenship categories have evolved over time this is now in practice understood to apply to New Zealand citizenship. While the government of the day sets rules about who can and cannot apply for citizenship, whakapapa transcends place of birth. Denying an automatic right of citizenship to second and third generation Māori born outside New Zealand could be seen as a breach of the Crown’s Treaty obligations, especially when this same group of people can still claim a stake in Māori land from overseas.32

If New Zealand decides to adopt a diaspora strategy, it will be important to consider the particular issues for the Māori diaspora and their rights under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. It is outside the scope of this report to recommend a specific solution, but these are significant questions to consider and resolve.

What do we know about the New Zealand diaspora?

The majority live in Australia, followed by the UK, US, and Canada

While we don’t have a precise figure for the total number of New Zealanders living overseas, various data sources can tell us something about who and where they are – and most of them are in Australia.

Since 1973, New Zealanders and Australians have enjoyed freedom of movement and the right to live and work in each other’s countries. It has long been a trend for New Zealanders to move ‘across the ditch’ in search of greater income and employment opportunities. In the 1970s and ‘80s, the numbers of New Zealanders moving to Australia soared as the income gap widened. Since the 1990s, as income growth between the two countries has largely fallen into step, New Zealand emigration to Australia has declined somewhat.33 However, Australian wages remain consistently higher than those in New Zealand.34 Since reaching a peak of around 60,000 in 2012, the number of New Zealanders moving to Australia each year prior to COVID-19 had halved to an average of around 30,000.35 Movements to Australia account for around 40% of all emigration from New Zealand,36 and it is estimated that around 600,000 people who were born in New Zealand now live in Australia.37 Some research suggests as many as one in six of all Māori now live in Australia.38 One thing to note about New Zealand’s diaspora in Australia is that most don’t return: of 630,000 departures to Australia over the past 20 years, only 34% were matched by New Zealanders making the return journey.39

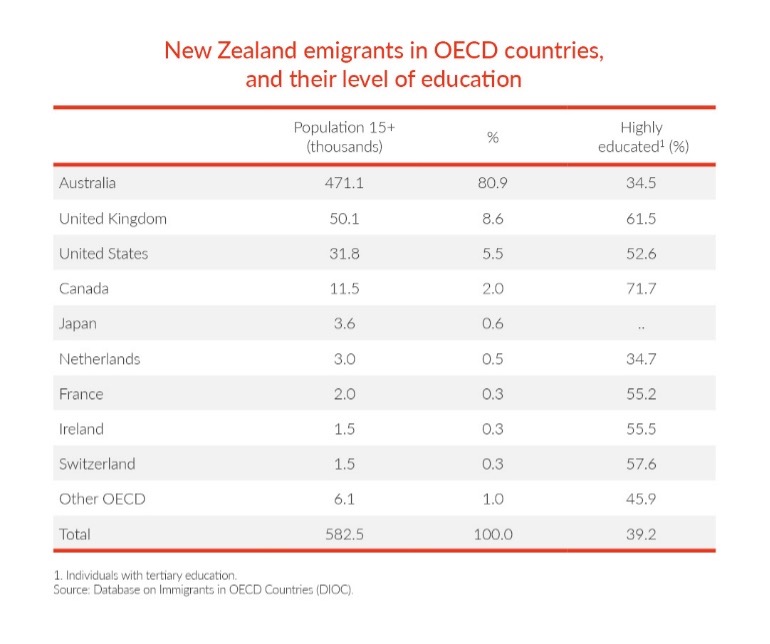

In 2015/16, there were 583,000 New Zealand-born people living in other OECD countries – 13.5% of the national population.40 After Australia, New Zealanders abroad were most likely to live in other English-speaking countries, especially the UK, USA, and Canada. Unlike those in Australia, New Zealanders living in these countries tend only to stay for short periods; 90% of departures to countries other than Australia in the last 20 years have been matched by New Zealanders returning.

They are more likely to be highly educated

New Zealanders living overseas are more likely to be highly educated than those living at home. Around 30% of the New Zealand population has a tertiary qualification, but this increases to around 40% of those living overseas. In total, around 15% of all New Zealanders with a university degree are living overseas. This effect is less pronounced for New Zealanders in Australia than it is in the UK, US, or Canada, which could be because skilled trades in particular command higher incomes in Australia than New Zealand – 28% higher when adjusted for differences in purchasing power – encouraging a greater share of New Zealanders with trade skills and qualifications to emigrate there.41

New Zealand emigrants in OECD countries, and their level of education

There are some tangible economic costs to such a high proportion of the tertiary-educated population moving overseas. One OECD working paper describes this as ‘a drag on the economy’, and notes that high-skilled emigration from New Zealand is likely to contribute to skills shortages, disproportionately reduce high-skilled employment, and contribute to lower productivity and living standards.42

However, it is important to note that in general, fears of a ‘brain drain’ of these highly educated New Zealanders are offset by the fact that our immigration settings favour highly skilled and educated migrants, resulting in what can more accurately be called a ‘brain exchange.’ The same OECD paper also observes that high-skilled immigration has more than offset New Zealand’s ‘brain drain’, noting that in 2015/16, immigrants made up 40% of the university-educated population in New Zealand.43

They can benefit New Zealand from afar

Having citizens or people with strong cultural and linguistic ties to home living in other countries can have benefits for the home country. New Zealanders living overseas acquire skills, contacts, and experiences that they can transfer back home, not only by moving home, but also by investing in New Zealand businesses, mentoring other New Zealanders abroad, and promoting trade links between countries. According to Julie Fry and Hayden Glass “the economics literature consistently shows that greater migration from a source country boosts trade in goods between the source country and the migrant’s host country.” Diaspora members create connections between producers and consumers in both countries, as well as buying products from their home countries and introduce them to new markets.44 Those who divide their time between New Zealand and another country in a pattern of ‘circular migration’ may be particularly effective at facilitating these connections.

Highly-educated and highly-skilled members of the diaspora may have the potential to assist New Zealand’s ‘frontier firms’ – those that are leaders in their field, both internationally and domestically – which in turn have the potential to help drive innovation, employment, and productivity in the New Zealand economy. Peter Wilson and Julie Fry note the challenge of connecting local frontier firms to the right global networks and recommend that the Government does more to use the skills, experience, and connections of the New Zealand diaspora to improve the productivity of actual and potential frontier firms and leverage potential growth markets for New Zealand goods and services.45

Results from Kea’s 2021 ‘Future Aspirations’ survey support the proposition that New Zealanders overseas are eager to help forge economic and cultural links between countries, with more than half of respondents who remained overseas saying they were looking for ways to maintain a strong connection to New Zealand.46

According to Julie Fry and Hayden Glass, the New Zealand diaspora may also be having a smaller impact than it could on New Zealand’s economic performance because most New Zealanders overseas are in countries with which we already have extensive trade links, like Australia and the UK. They suggest there is a greater potential benefit to New Zealand from a diaspora dispersed among a wider range of countries, noting that in particular we have fewer people than might be helpful in Asia and the Americas.47

They may be beginning to return in larger numbers

In 2020, expat organisation Kea surveyed more than 15,000 New Zealanders living overseas about their intentions to return to New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. This ‘Welcome Home’ survey found that 7% of respondents had already returned to New Zealand, and 49% intended to do so.48 This was followed up with another survey in 2021, which found that 13% had already returned, and 31% were intending to return. Of these, more than half planned to return in the next one to two years. 43% of those said they were influenced by the pandemic, and 23% specifically by the New Zealand government’s response.49

Aside from the pandemic, reasons given by respondents to Kea’s survey for wanting to return home reflected a strong sense of connection and belonging to Aotearoa New Zealand. The top four reasons were: to live close to friends/family; lifestyle/quality of living; a strong sense of home; and feeling proud to live in New Zealand.

Kea’s survey respondents were highly skilled, with many reporting experience in senior management positions, expressing an interest in starting or investing in a business on their return to New Zealand, and with desirable skills in sectors like technology and science, arts and the creative industries, healthcare, financial services, and infrastructure.

They could bring a boost to the economy and productivity

During the second half of 2020, there was a strong public narrative of New Zealanders returning in large numbers from overseas, memorably described by The Spinoff as a “once-in-a-lifetime talent shock […] a large group of returning New Zealanders, arriving in a compressed timespan, bringing a burst of international experience, capital and entrepreneurship to a country that has regularly lamented its stocks of all three.”50 At the time, we had only provisional data available about the number of New Zealand citizen arrivals during 2020. As noted earlier in this report, the migration data now available suggest we experienced more of a ‘brain retention’ than a ‘brain gain’ in 2020, but it is true that there has been a net gain in migrant arrivals of New Zealand citizens for the first time in more than 20 years. If this continues, there could be significant benefits for New Zealand, especially to help offset the fact that immigration, which provides a skills and education boost to the general population, has all but ceased entirely.

Because many returning New Zealanders are likely to be highly skilled and educated, they have the potential to boost innovation and productivity in our economy, including by increasing the scale of the economy; the share of the workforce that is highly skilled; and bringing an injection of international knowledge and experience.”51 Illustrating this effect, research in 2014 found that firms hiring greater numbers of recent immigrants and/or recent returnee New Zealanders tend to innovate more than other firms, thanks to the new perspectives and skills that these groups bring to the workforce.52

But some will require extra support

While New Zealanders overseas are on average highly skilled and educated, this is not, of course, the case for everyone. All New Zealanders have the right to return home, and some may require additional support when they do so; some may return in order to access health or social support that is not available to them in their adopted countries. Illustrating this, in May 2020 the “returned to New Zealand” category of those receiving Jobseeker Support reportedly increased from 5% to 12%.53

Some people are required to return to New Zealand against their will, as in the case of the so-called ‘501s’ – New Zealand-born citizens living in Australia who have been deported by the Australian government for failing the ‘character’ test in Australia legislation, sometimes without having lived in New Zealand since they were young children. Stuff reported in April 2021 that more than 300 New Zealanders have been deported from Australia since the borders closed at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.54 Many of these people have no friends or family support networks in New Zealand, most have criminal convictions, some have drug and alcohol dependency issues, and many require support to access housing, income, and employment. A high proportion are of Māori and Pacific heritage.

Who has been arriving during the pandemic?

Since August 2020, the New Zealand Government has been conducting a survey of the New Zealanders (and the small number of others) who have been arriving here during the pandemic, to get a better understanding of who is arriving, where they have come from, how long they intend to stay, and what their employment, housing, and family situations are like. This Survey of New Zealand Arrivals is intended to inform policy development in the future.

In June 2021, MBIE released provisional results from the survey for those surveyed between 1 August 2020 and 9 January 2021. Around 5000 people completed the survey during this time, and the data was weighted based on Stats NZ border arrival data to ensure the results were representative of the approximately 30,000 total arrivals during that period.

Some of the findings about these arrivals were:

- 72% were New Zealand citizens; 16% permanent residents; 6% Australian citizens; and 2% Australian residents.

- 9% were Māori. Of these, 17% could speak te reo Māori well or very well and 55% said Māori culture was important to them.

- 28% of non-Māori also said Māori culture was important to them.

- More than half were aged 18-39.

- 20% arrived with children.

- 38% had been living outside New Zealand for more than five years.

- Before coming to New Zealand, they had been living in Australia (32%), the UK (19%), Asia (12%), the US (10%), and Europe (4%).

- 51% said COVID-19 was a factor in their decision to come to New Zealand.

- Other reasons for coming included family or compassionate reasons (35%), lifestyle (21%), and employment (18%).

- 33% said they always planned to come at this time; 29% said they came sooner than planned.

- They were highly educated; 61% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 31% a post-graduate qualification.

- 60% were in some form of paid work following their arrival; 37% had found a new job in New Zealand, 13% were working remotely in an offshore job; 10% had returned to a job they already held in New Zealand, and 3% were on leave from an offshore job.

- 35% were not in paid work. Just over half of these people intended to seek work here.

- The top five occupations they were last working in overseas were: Registered Nurses; Chief Executives and Managing Directors; Advertising, PR and Sales Managers; Software and Applications Programmers; and GP and Resident Medical Officers.

- 39% were living in Auckland; 14% in Wellington; and 10% in Canterbury, with 1-6% in each other region.

- 32% were living in a place owned by family or friends, 27% in a rental, and 21% in a property they owned or partly owned.

- 79% said their living situation was suitable for their needs, but of those who said it was not, the main issues were overcrowding, cost, and size.

- 69% did not think they would need government assistance in the next six months and 12% didn’t know. Of those who thought they would need support, the top three needs were accommodation, income, and living expenses.

- 84% intend to stay in the region they are currently living in for 3 months or more.

- 24% would leave New Zealand if the global COVID-19 situation improved.

Removing barriers to return

Professor Paul Spoonley notes in his book, The New New Zealand, that “the New Zealand approach to this diaspora, both by government and as a matter of public interest, has been ambivalent. It is recognised that significant economic power and important connections reside within the diasporic community, but there is also a sense that these New Zealanders have somehow abandoned their homeland and that they are, by living and working in other countries, exhibiting disloyalty.”55 This version of ‘tall poppy syndrome’ is experienced personally by New Zealanders who have recently returned or are considering returning. Lamia Imam reports encountering this attitude in her Q&A on page 32 of this report, and several recently-returned New Zealanders described experiencing this ambivalence or even hostility from other New Zealanders upon their return in The Spinoff’s recent podcast series ‘Coming Home’.56 Illustrating an element of this experience, only 38% of those intending to return in Kea’s recent ‘Future Aspirations’ survey expected New Zealand businesses to fully understand and value their overseas experience.

The New Zealand government has had a migrant settlement and integration strategy since 2014.57 This strategy notes that well-supported migrants:

- settle and feel included faster;

- stay longer in New Zealand;

- help create a strong and vibrant community;

- help boost regional growth and wellbeing; and

- find it easier to participate in and contribute to economic, civic and social life.58

These are all outcomes that apply equally to the successful resettlement of returning New Zealanders. It would be useful to develop a parallel settlement and reintegration strategy for returning New Zealanders and develop specific advice and guidance around these matters to make their transition home as stress-free as possible.

For example, in Kea’s ‘Welcome Home’ survey in 2020, 31% of respondents said they would appreciate tax advice, and 35% advice about transferring overseas pensions and accessing Kiwisaver in New Zealand. 11% said they would appreciate advice about schools and childcare in New Zealand. The top three areas of support flagged by respondents to the government’s Survey of New Zealand Arrivals who thought they would need government assistance were accommodation, income, and living expenses. 35% of respondents to the same survey were not in paid work after arriving in New Zealand, and half of those were intending to look for a job. Many returning New Zealanders will be travelling with non-New Zealand partners and family seeking immigration advice and assistance.

In addition to general barriers like employment opportunities and the challenges of moving family, there are specific barriers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic that may be currently preventing more New Zealanders from returning. Factors such as the difficulty of booking Managed Isolation and Quarantine (MIQ) spaces, the high cost and risk of travel in the current environment, the challenge of securing flights, and the visa challenges of migrating with non-New Zealand family members have all been well-canvassed publicly.

As the New Zealand Government works towards re-opening the border and considers how isolation and quarantine are to be managed in the medium to long term, it is worth considering how return migration by New Zealanders can be facilitated and encouraged as part of our ongoing pandemic response. A public indication at senior government level that returnees are welcome would be a good place to start.

The case for a diaspora strategy

As a nation of only five million people, an additional million people with often meaningful cultural, social, and economic links to Aotearoa New Zealand in other countries is significant, and there is more that could be done not only to encourage some of these New Zealanders to return, bringing their skills, ideas, and capital, but also to forge stronger links with those who remain overseas. As Julie Fry and Hayden Glass note, “Governments can do more to remove obstacles by taking specific actions to understand where and who their diaspora populations are, build solid relationships with diaspora partners and facilitate their involvement in the country of origin, and consolidate their sense of belonging.”59

Some governments have begun to pay more attention to their diasporas, thanks in part to the ways in which technology has facilitated greater ongoing connections between people living overseas and their home countries. Ireland, one of only two other OECD countries with a diaspora proportionally larger than ours, is emerging as a centre of best practice for diaspora management, and recently developed an ambitious diaspora strategy for 2020-2025, overseen by a Minister for the Diaspora.60 We advocate the adoption of an equivalent strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand.

At present, Kea New Zealand, in partnership with New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment does valuable work facilitating trade and innovation connections with and between New Zealanders overseas and at home.

This is important because, as Julie Fry and Hayden Glass observe, “New Zealanders who maintain personal links with New Zealand and a sense of shared identity are more likely to be interested in helping New Zealand. They might see a relationship as useful to their economic interests or to their sense of identity or personal projects. They might invest in New Zealand, run businesses here or contribute to projects that help develop the country. But they can’t do it on their own.”61

Current activity to develop and build on these connections, both formal and informal, could be better supported and resourced if underpinned by a strategy that proactively identified an engaged diaspora as a government priority, and set out specific and measurable goals and actions for how this will be achieved.

One focus area of the Irish diaspora strategy is language and culture, in which it commits to the promotion and teaching of the Irish language abroad and supporting Irish cultural organisations, associations, and festivals around the world. It is interesting to consider what a diaspora strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand might look like from a Te Tiriti o Waitangi / Te Ao Māori perspective. What support could be given to promote the use and teaching of te reo Māori overseas? How many Māori organisations are operating in other countries and how can these groups be supported to connect with each other and their whānau, hapū and iwi in Aotearoa? Could respectful, appropriate, and well-resourced dissemination of Māori culture abroad, by Māori be supported? These would be productive questions to explore, in partnership with Māori, as part of the development of a diaspora strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand.

Electoral implications

Having a large New Zealand diaspora also raises some interesting questions about the extent to which overseas New Zealanders can and should have a say on politics and policies at home. At present, people can vote from overseas in New Zealand’s local and general elections if they are a New Zealand citizen who has visited New Zealand in the last three years, or a permanent resident of New Zealand who has visited in the last 12 months. The 2020 general election took place early enough in the COVID-19 pandemic that the border closure and MIQ requirements are unlikely to have prevented many overseas residents from voting, but depending on how long the restrictions are in place, by the 2022 local and 2023 general elections, there are likely to be a significant number of New Zealand citizens and permanent residents unable to vote because the pandemic has made it too difficult to visit New Zealand in the required time.

The Electoral Commission recognised this in its report on the 2020 General Election, recommending, among other things, that consideration be given to “legislative change to the overseas voting eligibility criteria to address situations where voters have been prevented from returning to New Zealand by circumstances out of their control, such as a pandemic.”62 This matter is currently before the Parliament’s Justice and Electoral Select Committee as part of its Inquiry into the 2020 General Election and Referendums.

Some campaigners go further and recommend not only the creation of a ministerial portfolio with responsibility for the diaspora, but the creation of specific representation in Parliament for overseas constituents.63 This might not be as outlandish as it first sounds; at least 11 other countries, including France, Italy, Ecuador, and Algeria, have some form of direct political representation for external voters in their national legislatures,64 although it is hard to imagine a scenario in the near future in which there would be political will for such a change in Aotearoa New Zealand.

“Coming back was always part of my plan”: Q&A with recent returnee, Lamia Imam

Lamia Imam was born in Christchurch and grew up in Bangladesh and the US. She studied at the University of Canterbury and worked in the New Zealand Parliament and Ministry of Justice before moving to the US in 2013 to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Texas at Austin. She currently works in Communications for Dell Technologies. She and her American husband, Cody, relocated back to New Zealand in March 2021.

What was the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic like for you and your community in Austin?

In February of 2020, my husband Cody and I were in New Zealand for our honeymoon. We attended a wedding in Auckland in the first week of March and then proceeded to do a road trip across the country. Cody had never been here so it was a chance for me to show off the country and convince him that we should relocate. As we were travelling through New Zealand, I faced an immigration issue with the US Embassy, and while they were obtaining more information from the State Department, New Zealand entered Level 4 lockdown. We didn’t return to the US until May 2020 after my visa issues were resolved, and New Zealand was in level 3.

When we went back to Texas, in the absence of adequate official guidance, we imposed “Level 4” on ourselves. After watching New Zealand bring the COVID numbers down to zero while the virus was continuing to spread in the US, we decided we could not trust US officials to keep us safe. From May 2020 to March 2021, we were mostly at home. We had groceries delivered, did zoom meet-ups, and stayed in our bubble of two. From time to time, we did open our bubble with family and friends after taking extensive precautions like 14-day quarantine or masked outdoor encounters. Some of our friends found our measures extreme, particularly when states started opening up, and it led to some difficult conversations around boundaries and risk management. Still, we felt confident in our decision, and as far as we know we never got COVID. As the months progressed, we went from never knowing anyone with COVID, to friends getting sick, to friends being hospitalised. The numbers were dangerously high following Thanksgiving and Christmas 2020, and it was difficult to watch the death toll rise while the state and federal governments effectively gave up and waited for the new administration and rollout of vaccines.

What made you decide to come home? Was it a hard decision?

Coming back was always part of my plan. I moved to Texas because I wanted to pursue higher education without incurring further student loans. I was glad that I got admission to a top-tier policy school and was able come out without further debt. However, I missed New Zealand and my life here. I missed the culture and the geography of the country. I missed my community, and I was always eager to return. It was not a hard decision, but the move itself during the pandemic was extremely hard. It is also a completely different ball game when you are bringing a partner back who has never lived outside of Texas. From shipment of our household belongings, to arranging immigration for Cody, to finding employment and a place to live, it has all been incredibly draining.

Can you describe the initial experience of coming out of isolation and re-joining ‘business as usual’ in New Zealand? How strange was it? What stood out in particular?

Being dropped off at the airport and seeing people without masks talking to strangers indoors was jarring and pretty scary but also surreal. We felt like we had time travelled back to March 2020.

What else struck you about NZ after some time away? Were there any major changes that stood out to you, or things you had forgotten about?

From memory, I never had any issues with buses in Wellington, as I didn’t own a car and relied on buses and walking. This seems to have changed in the last eight years and more people seem to be driving. The rising house prices – which were already out of my reach when I left – are also extremely hard to swallow.

Do you think New Zealanders understand how traumatic it has been to live through extended lockdowns in places with high infection and death rates? What do you wish people understood better?

I don’t think New Zealanders truly understand the trauma of being abandoned by your government and I honestly don’t think I want them to. It is better that they enjoy the benefits of having a government that worked to prevent deaths without guilt. However, I do wish that New Zealanders did not blame people in other countries for not ‘doing better on their own’. I was recently talking to a friend about “our response to covid” compared to America’s and he shot back “what do you mean our response, you weren’t part of it”. I meant New Zealand’s response as a New Zealander, but it was really clear to me how some New Zealanders at home think it is our own fault if we struggled with the pandemic outside New Zealand. I think Kiwis abroad – particularly people who cannot come home for many reasons – are struggling with the feeling of being side-lined and mocked for leaving. It is extremely difficult to weather this pandemic if you have low incomes or are isolated without help and clear messaging from the government. For these reasons, I find the ‘Team of Five Million’ language very isolating.

What has your experience of finding work here been like? Are there equivalent roles to the one you left? Do employers understand and value the skills you gained overseas?

Before I left New Zealand, the narrative was that overseas experience would be valued here and that to be competitive you had to leave New Zealand. But now that I am back it seems there is also a level of resentment towards returning New Zealanders, and I think some people perceive us to be entitled. I was fortunate to find a role in New Zealand with my US-based company and transfer, however, despite being a Software Developer which is on the skills shortage list, Cody has found that wages are not comparable (but we expected and prepared for this).

What has his migration experience been like?

Coming from a visa waiver country has made his migration easier than others, but dealing with Immigration New Zealand has been the most difficult aspect of this move.

Has the experience of coming home lived up to your expectations? What have been the best and worst things about it?

Despite some challenges, coming home has exceeded my expectations. I expected to miss the convenience of living in the US (wider roads, central heating, more choices, and faster delivery of internet shopping) but I don’t really miss any of it. Reconnecting with friends has been the best part of being back. The worst thing without a doubt is the housing situation, particularly in Wellington.

Would you advise someone in a similar situation to come home?

I would advise anyone coming back to take stock of their community connections, and consider whether they are stronger at home or abroad. One of the reasons I left Texas is that I felt disconnected from my community.

Part 3: Ready for the future

As noted in Parts 1 and 2, COVID-19 notwithstanding, Aotearoa New Zealand’s population is growing, diversifying, ageing, and urbanising. We may be at the start of a new trend towards net positive migration of New Zealanders returning from overseas, and there are strong economic, cultural, and social reasons to encourage this. At some point, our borders will also reopen, enabling new residents to move to Aotearoa from other counties. We don’t know what the immigration policy settings will look like when they do, but there are strong indications to suggest net migration will not return to the highs experienced immediately prior to the pandemic. While there is still a great deal of uncertainty about what Aotearoa New Zealand’s post-pandemic future will look like, we know enough to anticipate and prepare for a number of key policy challenges, not least of which is how we will ensure this growing, urbanising population is affordably, accessibly, and sustainably accommodated in our cities and towns, especially Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland).

There are few policy levers we can directly pull to encourage return migration, but we can at least make the prospect of returning more appealing by making sure our cities and towns meet the standards of the global cities many New Zealanders overseas will have lived in: cities with enough affordable, accessible, healthy homes for everyone; with rapid, reliable, affordable public transport; with green transport infrastructure that reduces congestion and encourages active modes; with plentiful green space and urban design that encourages connected communities. This Part focuses on preparing our cities and towns for the future.

Preparing our urban infrastructure

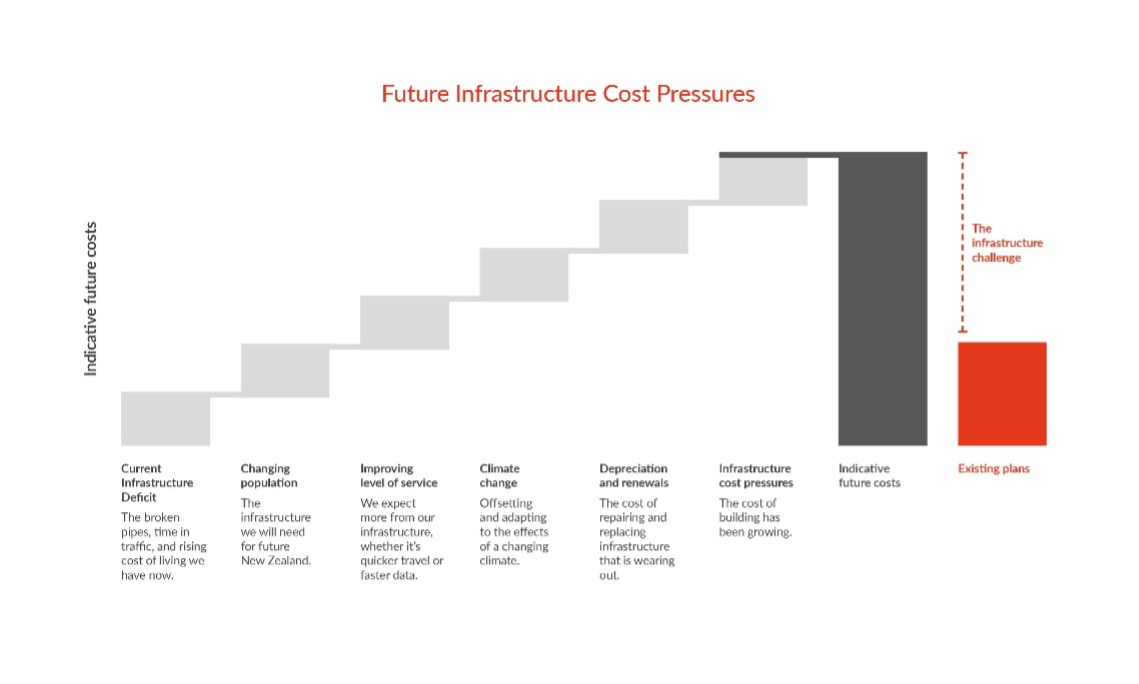

For some years, a combination of factors including historic underinvestment, population growth, climate change, cost pressures, and depreciation has combined to create a gap in the provision of the core infrastructure of Aotearoa, so that there is now a significant infrastructure challenge.

Analysis from Infometrics shows that Aotearoa New Zealand’s per-capita investment in infrastructure over the last 40 years has consistently been below that of Australia, Canada, and the US – and generally lower than the UK. This underinvestment means the country’s infrastructure is struggling to keep up with the need to replace aging assets and upgrade capacity to meet growth.

Delaying or cancelling investment in infrastructure is a false economy. Infrastructure that isn’t sustained leads to serviceability issues (leading to increased lifecycle costs) resulting in a decrease in infrastructure network value without a corresponding decrease in depreciation.

Future Infrastructure Cost Pressures65

The New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, Te Waihanga, was established in September 2019 with a mandate to lift infrastructure planning and delivery to a more strategic level and by doing so, improve New Zealanders’ long-term economic performance and social, cultural, and environmental wellbeing.66 Te Waihanga is currently working with central and local government, the private sector and other stakeholders to develop a 30-year infrastructure strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand

One of the three core ‘Needs’ identified as a priority in the Commission’s draft strategy document is the need to ‘Enable competitive cities and regions.’ According to the Commission, our cities currently face several problems that constrain their ability to deliver high living standards and compete for global talent. These include:

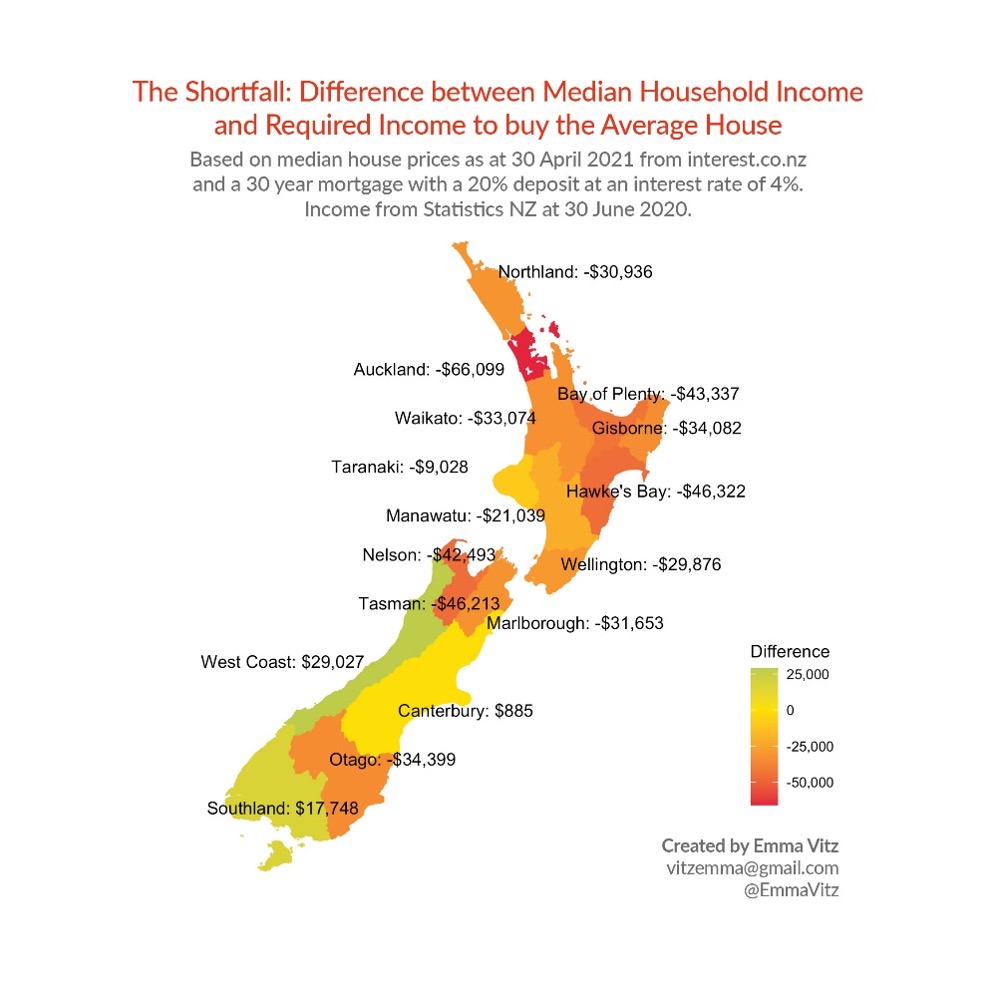

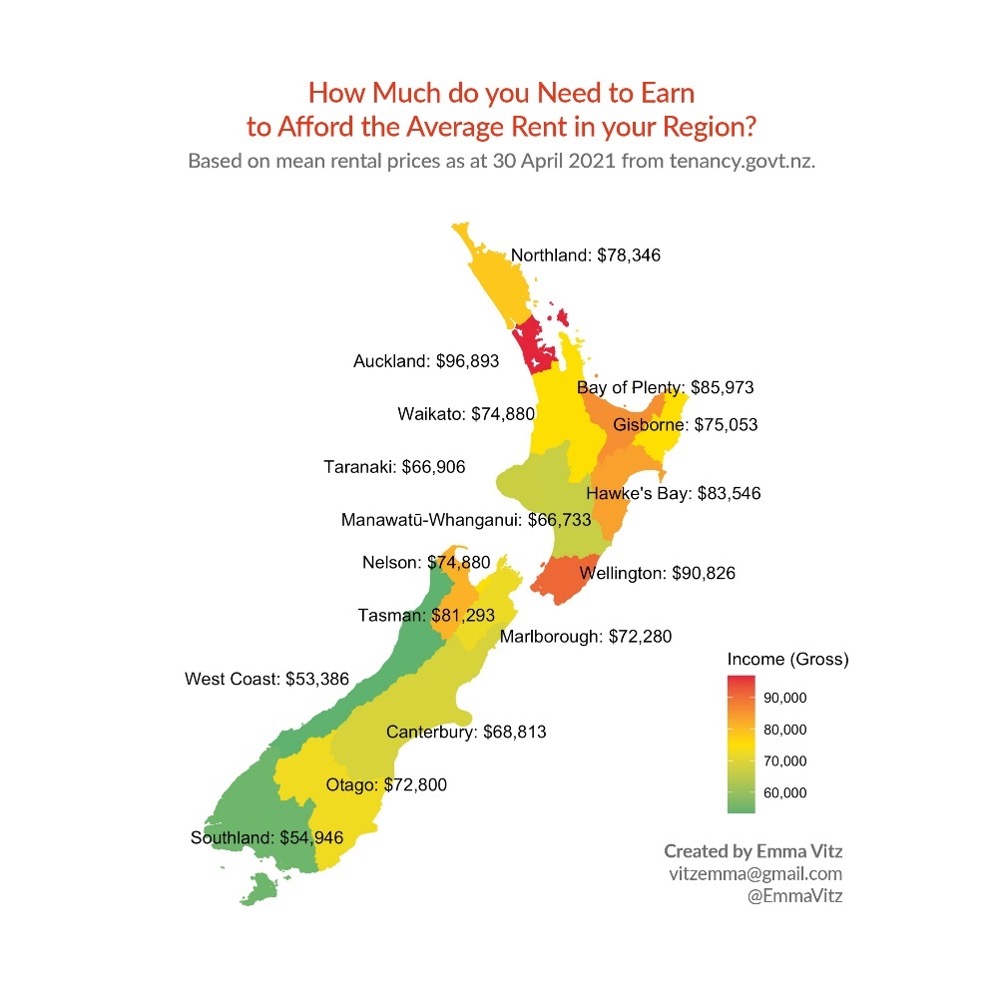

- Extremely unaffordable housing, especially in fast-growing cities, and broader issues with housing quality, including standards of heating, ventilation and dampness;

- Comparatively high levels of traffic congestion, poor availability of public transport and walking and cycling options, and urban design that leads to poor quality-of-life outcomes;

- Limited urban wage premiums. Higher incomes in Auckland and Wellington are largely offset by higher housing costs, pushing people to live in other places that offer lower wages. Conversely, those on nationally set incomes (such as nurses, teachers and police) face higher housing costs than their peers elsewhere.